Features

Operations

Cargo airships for Manitoba?

David Harper, grand chief of the Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO), knows first-hand how difficult it is to live in Manitoba’s far-flung reservations and remote communities.

March 3, 2014 By Bill Zuk

David Harper, grand chief of the Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO), knows first-hand how difficult it is to live in Manitoba’s far-flung reservations and remote communities. With nearly every commodity shipped or hauled up north through winter roads or flown in by an expensive network of regional air services, the cost of a two-litre carton of milk can soar up to six dollars or more. More crucial is the exorbitant price of building materials resulting in a housing crisis in the North.

|

|

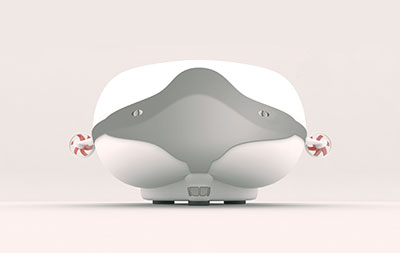

| The Aeroscraft Dragon Dream airship is a rigid-type cargo airship designed to carry 66 tons of cargo or more for both military and civil applications. Its first flight is scheduled for 2016. Photo: Aeroscraft

|

This explains why Chief Harper, representing Manitoba’s northern chiefs organization, was standing next to Manitoba transportation expert and airship advocate Dr. Barry Prentice at the University of Manitoba’s recent unveiling of an experimental MB80 airship, pledging to work together for the development of cargo airship technology. Although the MB80, dubbed Giizhigo-Misameg (“Sky Whale” in the Oji-Cree language), is an experimental blimp built by Buoyant Aircraft Systems International and ISO Polar, headed by Dr. Prentice, the 25-metre prototype will test out the potential for future cargo airships in the North. Harper said he believes airships could be a reality in Manitoba in three to five years.

The first tangible evidence of the new collaboration of northern stakeholders and ISO Polar was an initiative of the Wabung Development Limited (the MKO’s business development arm) in association with MKO and the Government of Canada in co-sponsoring the “Remote No More: Cargo Airships Conference” this past Oct. 9-10 in Winnipeg. The merging of stakeholders, government and industry also involved the traditions and heritage of the First Nations people with participation from elders and community members, incorporating the unique aspects of northern life into the proceedings.

As Dr. Prentice explained, “It’s the Manitobans who live north of 65 who understand that transportation is an integral and everyday problem. The lack of reliable, cost-effective transport delivery systems has created cost-of-living realities that have kept generation after generation in preventable poverty.”

Building on the recent 2013 Cargo Airships For Northern Operations workshop held at the University of Alaska, Anchorage, this past July, “Remote No More” brought together the leading exponents of the Lighter-than-air (LTA) industry with the people who live and work in Manitoba’s north. In order to set out a real-life scenario, each airship company in attendance was presented with a homework assignment – hauling 50 tonnes of building supplies for a northern school. Not surprisingly, each presentation at the event showcased a potential winner, albeit focusing on the specific advantages of a particular design.

Dr. Prentice and Kevin Carlson, former MKO housing capital and transportation advisor, acted as co-chairs and set up the parameters of the event as being a “working conference.” Chief Ron Evans, Grand Chief for the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, set the tone of the assembly as being “… important for us to do what we can to ensure that our people are healthy and have the best conditions of life. It’s time we look at all solutions and although I have yet to see a cargo airship in Manitoba, we need to look at this.”

Throughout the two-day event, the northern chiefs were active participants in Q&A sessions and panel discussions linking them with the shippers, stores and air transport representatives who work in the north. While the North West Company took an active role, air carriers were more limited in their participation, although offering data and background information as part of a panel discussion. Other aspects of airship operation were also examined, including research and development in an emergent industry as exemplified by the work of Canada’s National Research Council, regulatory considerations worldwide and infrastructure needs for manufacturing and northern operations.

Other stakeholders included Manitoba Hydro and Centreport Canada, but noticeable in their absence, were government representatives, especially from federal departments such as saying Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, Ministry of Transport and Natural Resources and Environment, all invited but unable to attend. Alaska state senator Lesil McGuire, on record that “cargo airships could be a game changer in Alaska” was also invited to the conference, but was a late no-show. Representatives from NASA Ames were also scheduled to attend but fell victim to the effects of U.S. congressional sequestration.

The winter road dilemma

Freight shippers in Canada’s North will strive to utilize the most cost-effective means for transport, and where the locations have access to sealift, rail or a permanent road, remote and isolated communities can be served adequately. Many of Manitoba’s remote communities, however, including 16 reserves of the MKO, depend on seasonal winter roads, often inaccurately described as “ice roads.” In the ESLW (East side of Lake Winnipeg) region, 69 per cent of the total freight tonnage is transported by truck. In order to minimize freight costs, the majority of the shipments north are scheduled during the winter road season.

|

|

| Financial assistance from military programs such as the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) program has spurred the nascent airship industry and helped in the creation of Lockheed Martin’s P-971. Photo: Lockheed Martin

|

The approximately 2,500 kilometres of winter roads are temporary seasonal byways carved through bush and across frozen muskeg, lakes, rivers and waterways to temporarily connect remote regions with the rest of the province. Typically, winter roads had been open from mid-January until sometime in March, but seasonal changes have considerably shortened their usefulness as well as created dangerous conditions as the roads deteriorate.

According to Larry Halayko, a director with the Manitoba Infrastructure and Transportation Department, “The warm start to the winter certainly was a challenge, to get out there and get that frost into the ground and get the ice built up.” With later opening dates for some of the roads and, initially, load restrictions, it was difficult to haul the customary “year’s worth” of supplies such as food, fuel and construction materials, to the north.

A 2013 study, “Assessing the Cost Competitiveness of a Cargo Airship for Freight Re-Supply in Isolated Regions in Northern Canada” undertaken by graduate student Matthew Adaman for the Department of Supply Chain Management, University of Manitoba, noted, “less than 30 days utilization is observed in half the years since 1997.”

The solution proposed for the region by the Manitoba government is to build a permanent 872-kilometre, all-weather road system, the East Side Road. It is an estimated $2 billon-plus, 30-year project with an unannounced start date. Tackling a major infrastructure project such as this comes with its accompanying environmental and technological challenges. In considering other Canadian remote and Arctic regions, however, a permanent road system will not even be an option.

The case for airships

The only mode of transportation available year-round in the north is air transport. According to Adaman, with modal choices constrained by the seasonal availability of truck and barge operations, northern and remote communities have to rely on air transport for approximately 60 to 75 per cent of the year. In addition to its use in search-and-rescue (SAR) missions, specialized surveillance and monitoring, and emergency medical evacuation – and despite its high costs – air transport has also been used for shipping food and general merchandise. Adaman’s study showed that in 2011-12, actual cost of freight supply and re-supply by air was 625 per cent more than shipping by winter road or via permanent road access.

The near-collapse of the winter road system has led to a crisis in Manitoba’s north where air transport is presently the only option, albeit a costly and similarly unreliable delivery system due to inclement weather. Two major shortcomings of conventional aircraft are their high operating costs and their need for extensive supportive infrastructure including runways, hangars and repair facilities.

The prohibitive costs of northern transport have led to a renewal of interest in what is the world’s oldest aviation technology: Lighter-than-air (LTA) designs. Despite the public perception that after a series of notable air disasters in the 1930s, LTA technology was no longer feasible, airships in various formats continue to be successfully employed in niche roles such as advertising, sightseeing and surveillance, but have never been used in a freight transportation role.

Airship technology on display

The lineup present at the “Remote No More” conference was a veritable “who’s who” of the fledgling airship industry that included Aeros Corporation, AeroVehicles Inc., Augur RosAeroSystems, Hybrid Air Vehicles, Lockheed Martin, Ohio Airships/Dynalifter International and Varalift Airships PLC. One notable absentee was Airship do Brasil, listed in the program, but whose representative was not present during the formal part of the presentations. A genuine airship celebrity was also present in the form of the former Goodyear Blimp pilot and current Aeroscraft test pilot Corky Belanger.

|

|

| AeroVehicles Inc. of Santa Maria, Calif. is currently developing the AeroCat R40, a hybrid aircraft that could prove useful in several capacities in Canada’s Far North. PHOTO: AeroVehicles Inc. |

Although no production examples exist, several cargo airship developers have successfully flown a modern cargo airship prototype. The main types of airship are non-rigid (blimps or aerostats), rigid (airship designs featuring an internal framework) and semi-rigid (designs using a spine or keel with powerplants, flight control systems and ballonets/cells attached). All contemporary airship designs in development are “hybrid,” combining features of an aircraft, hovercraft and helicopter with that of an LTA.

A number of significant questions need to be answered in order for the industry to consider cargo airships as a serious solution to northern air transport. The first is the fundamental one: can a cargo airship lift enough to be cost-effective, especially when loading and offloading has to involve the shifting of massive weight? Earlier dirigibles depended on a mooring system to tether the airship during ground operations. All modern airships have a buoyancy control system to allow efficient loading and off loading, and have proven their individual systems in tests that have involved proof-of-concept demonstrators. Hybrid Airship program manager Dr. Robert Boyd from the Lockheed Martin “Skunk Works” says, “If it’s about the science, the science works.”

Airships that are now in development offer some other advantages over conventional aircraft that are typically in service in Canada’s North. Giant airships, larger than the Royal Canadian Air Force’s current C-17 Globemaster III with its 164,900-pound payload, will lift hundreds of tons, although flying at slower speeds and lower altitudes.

The next question that must be answered is this: does it make sense economically? The rationale for the cargo airship rests on its theoretical cost advantage over other modes of transport when operated in isolated regions. Adaman estimates a 30 per cent saving over air transport, in line with a 2011 study by Maj. Philip W. Lynch, United States Air Force, that compared projected cargo airship deployment to a combat environment as more cost-effective than C-17 or sea-lift options.

In the daunting conditions of the Russian hinterlands, many of the remote Siberian communities no longer can depend on regular service by air, as the runways over a decade of disrepair and neglect are no longer sustainable, with large helicopters employed for supply missions. The cost effectiveness of cargo airships compared to helicopters such as the Mi-26 is readily apparent with an estimate of “$150 to $200/hour compared to $1,500 to $4,000 for helicopters,” Sergei Bendin of the Russian Aeronautical Society noted in 2009.

Cargo airship service would theoretically be available all year, and this would lead to indirect economic benefits. For example, commodities that are today shipped in large quantities during the winter road season and stockpiled throughout the year could instead be shipped year-round. Dr. Prentice also counters that “airships could also offer occasional passenger capability as well as the opportunity to return with partial or full back-hauls in order to better support the economy of the region.”

Safety first: are airships safe and reliable?

One of the significant advantages to the Augur RosAeroSystems line of specialized LTA aircraft is that each design is built to the demanding requirements of operating in Russia, including Siberia. The company’s latest Atlant cargo airship with variants flying with 16-, 60- and 170-ton payloads, has an aerodynamic shape consisting of composite materials providing additional lift, stability in strong side gusts, and low loads in flight and on the ground, with the composite shell allowing for “hangarless” operation. Company president Gennady Verba clearly linked the types of weather and ground conditions in Siberia to that of northern and Arctic Canada. The Atlant is built to meet the following demanding specifications:

- temperature extremes from 20 down to -50 C

- 40- to 50-knot winds, including side gusts

- snow load of up to 100 kilograms/square metre

- ability to fly in icing conditions

- 100 days a year of Polar Night

- lack of ground infrastructure

AeroVehicles CEO and co-founder Bob R. Fowler indicated that Aerocat 20/40, similarly, is designed to operate in Antarctica and its design features a nosecone that “will shed snow, ice and ice particles” and an aerodynamic shape that will create lift as well as be impervious to weather conditions it will face in one of the most challenging environments on Earth.

Varialift Airships PLC CEO and founder Alan Handley dealt with the design choice of an all-aluminum concept: “History shows us that to carry heavy loads over long periods of time and distance, a strong, robust vehicle is required,” he said. “As demonstrated, ships at sea, railways, aeroplanes and now airships. Aluminum is ideal for containing helium with a minimum loss of helium, long working life, repair away from base with mig/tig process and recycling after a long lifespan.”

The question of safety still remains, and in designing the Atlant, one controversial option was advanced – the use of hydrogen as a lifting gas, already in use in Russia where UAVs and unmanned aerostats operate under a special provision administered via the Russian State Fire Service. Citing ongoing research on inhibiting agents (hydrogen phlegmatizing inhibitors), Verba has shown promising results in tests. The use of the readily available and inexpensive gas compared to increasingly depleting stocks of helium, provides for a performance advantage over any other form of LTA. Yet, Verba conceded that the use of hydrogen may be abandoned due to customer resistance, and that the Atlant series can operate with the inert, but safe helium.

So, is there government support for airship operations? Ron Hochstetler, an LTA engineer, with Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC), has dealt with the need to modernize both the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and Transport Canada regulations to meet the needs of a new hybrid airship category. One significant aspect of the development of the Lockheed P-971 cargo airship was that its FAA certification process has “covered 90 per cent of all the worldwide designs.”

Regulations also have to apply to operational needs. When AeroVehicles Inc. began the process of certification of the airship pilots in Alaska, the FAA countered with “there are no existing regulations to certify airship pilots in the U.S.” In Canada, the airship pilot licence requirements in CARS 421.25 similarly need a drastic overhaul, as ISO Polar’s Dale George, the only Canadian pilot certified for airship flying, can attest, after being first to qualify as a “balloonist.”

Financial assistance from military programs such as the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) program has spurred the nascent airship industry and has led to the landmark hybrid cargo airship program in 2006, the Lockheed Martin P-971, a scaled prototype of the projected 70-ton-payload SkyTug non-rigid hybrid design. DARPA also financed the similar Hybrid Air Vehicles (U.K.) Airlander design, developed in partnership with Northrop Grumman. Both projects faltered when government assistance did not get extended beyond the research and development phase. With proper financing, the civil versions of the projects can be revived.

Cost and infrastructure: Is it feasible?

Nearly all the airship designs in development are also considered hybrid as the characteristics of aircraft and even helicopters are incorporated, with little or no requirements for ground infrastructure if hovering or short take-off landing (STOL) or short take-off and vertical landing aircraft (STOVL) characteristics are built in. The combination of buoyant lift control, high cargo carrying capacity and greatly reduced ground requirements means the cargo airship should theoretically be able to move a unit of cargo over a unit of distance at a lower cost than conventional aircraft. Some designs feature a hard shell casing that allows for a hangarless operation, although the problems of manufacture of a large aircraft must still be considered. Dr. Boyd mused that when competing with conventional aircraft, the odds are still stacked against cargo airships: “The risks and costs of building an infrastructure are still high.”

Aerospace experts have indicated big airships struggle with both regulatory issues and a costly infrastructure, including hangars and production facilities. Richard Terry, engineering division, from Arup Canada, one of the world’s most prestigious engineering firms, provided a “cautionary tale in the form of the CargoLifter experience” where costs and financial problems crippled a major program. Aerium, the immense production hangar built to accommodate the CL160, was abandoned when CargoLifter AG went bankrupt in mid-2002.

John Spacek, CentrePort Canada’s vice-president of planning and development, offered an intriguing possibility at “Remote No More” for cargo airship development. CentrePort Canada on the outskirts of the Winnipeg James Armstrong Richardson International Airport complex, is the only inland port in Canada offering business single-window access to Foreign Trade Zone benefits, much like the San Luis Free Trade Zone in Argentina, a key component of the AeroVehicles Inc. long-term plan.

In the final presentation of the two-day conference, Ohio Airships/Dynalifter International president Craig Zimmerman described the unique Dynalifter project, with a 1/6 scale prototype now entering flight-testing. Zimmerman made an unexpected announcement that the Dynalifter was coming to Manitoba in 2014 and that preliminary studies had pinpointed a possible manufacturing site in the abandoned Saunders Aircraft Company plant in Gimli, Man. The airport and industrial park would also become a centre for test flights and proving trials, with a later establishment of a supply depot for future northern operations.

Will cargo airships take to the skies soon?

After flying airships for almost 40 years, Belanger is one of the most experienced LTA pilots in the world. Belanger was hired by Goodyear and spent more than a decade flying the iconic airships – including a star turn as one of the pilots in the iconic Black Sunday film in 1977. Since leaving Goodyear, Belanger also has flown airships for brands like Budweiser, MetLife, Sea World, Farmers, and dozens of others. He holds a Multi-ATP License from the FAA, and has more than 15,000 hours at the helm of a dozen different airships, flying for companies on five continents. He is now the test pilot for Worldwide Aeros Corporation where, for 13 years, he has worked closely with the engineering team to optimize pilot controls and ergonomics, while also developing flight procedures and co-ordinating pilot training. As the test pilot for the company’s new hybrid airship series, he flew the Aeroscraft proof-of-design technology demonstration vehicle in 2013. Corky Belanger Jr. now continues the family tradition as the pilot of the Goodyear Blimp, “Spirit of Innovation.”

|

|

| Manitoba transportation expert and airship advocate Dr. Barry Prentice of the University of Manitoba is a staunch believer in the value of airships to the Manitoba economy. Photo: Bill Zuk

|

“I’ve witnessed both rigid and non-rigid types and their advantages and disadvantages to airship design,” he says. “The industry has moved forward slowly but constantly making some airships very advanced in comparison to the airships prior to the 1970s. Some of these advancements include tail configurations to include X, inverted Y and +. Others are the implementation of ‘vectored thrust’ allowing the pilot to control the angle of thrust in relation to the angle of incidence, allowing short take-off capabilities and tail thrusters, allowing greatly increased control during takeoff and landing at low airspeeds. The one problem that engineers had not been able to overcome is the offloading of passengers/cargo without an established infrastructure. That fact, in itself, has been the biggest drawback to the future of airships. The inability to offload goods without having ballast to offset the loss of load has been something that many companies have tried with no success. With the management of ballast control as used in the Aeroscraft, it appears now that problem has been overcome.”

The road ahead

“Remote No More” showed that cargo airship technology has matured and now requires the commitment of regular service with an established service provider and shipper and government investment to launch airships into Canada’s northern skies. At the end of the formal proceedings, the MKO representatives spent the following day in consultation with airship industry representatives, many of the parties agreeing to continue the dialogue in the coming months.

Recently, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Transport, Infrastructure and Communities in its Innovative Transportation Technologies report, made three recommendations on airships. The first recommendation was for Public Works and Government Services Canada to consider a “pilot project” involving the transport of non-urgent goods to remote destinations. The test run would involve proving the technology was safe as well as commercially viable. A push for international regulations for airships and hybrid air vehicle technology was also part of the report. On Feb. 15, Natural Resources announced a grant of $2.2 million to support one airship company.

In related news, on Nov. 18, Aeros Corporation announced it had signed a memorandum of understanding with Canada’s CAE, a global leader in simulation and training for civil and military aviation. The MOU specifies that the two principals will explore potential business relationships leading to the development and delivery of simulation-based training for the new Aeroscraft series.

Finally, on Nov. 21, Cliffs Natural Resources Inc., a major U.S. player in northern Ontario’s Ring of Fire project says it’s indefinitely suspending its chromite project in the mineral-rich area. The company blames an uncertain timeline and risks associated with developing infrastructure. Building roads, threatening a fragile biosphere and negotiating with First Nations people were all cited as stumbling blocks. But imagine what a fleet of airships could have done in hauling the equipment and building supplies needed to jumpstart the project? It’s but one example to illustrate the potential value airships can bring to help drive the Canadian economy.