Features

Airlines

Fuel

Flight shame, climate change

How the consumption of Aviation fuel has changed and emerging trends

January 20, 2020 By Jan Ditzen and Erkal Ersoy

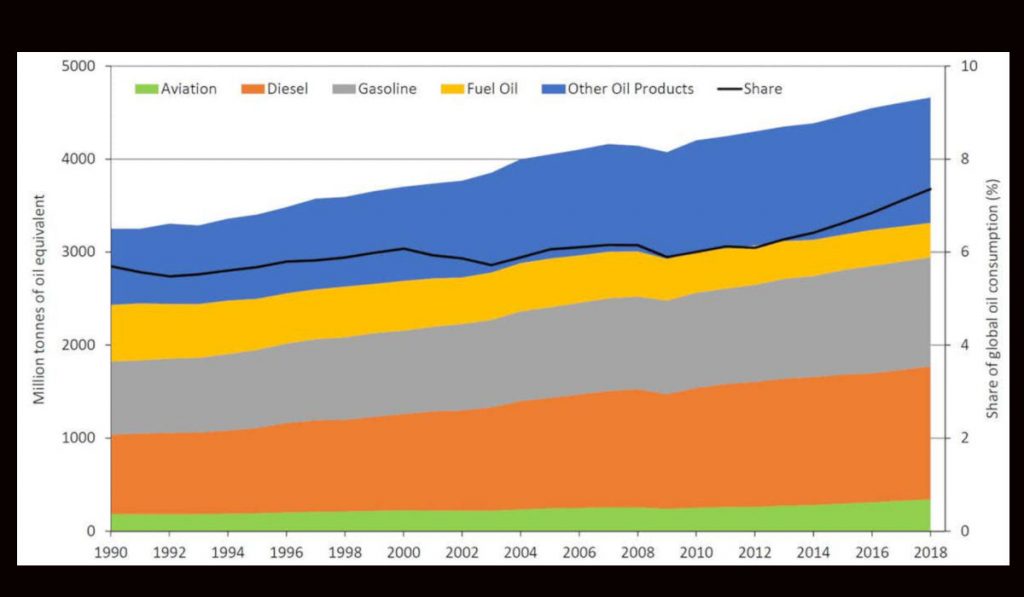

Global oil consumption by fuel type. Consumption measured in million tonnes of oil equivalent (mtoe) on the left axis, and share of aviation in global oil consumption on the right axis. (Image: Jan Ditzen, The Conversation)

Global oil consumption by fuel type. Consumption measured in million tonnes of oil equivalent (mtoe) on the left axis, and share of aviation in global oil consumption on the right axis. (Image: Jan Ditzen, The Conversation) Flygskam – the Swedish word for flight shame – describes a phenomenon that has taken off around the world, as travellers face growing pressure to reduce their carbon emissions by switching to alternative modes of transport. Climate activists have denounced air travel, settling for boats, trains or, at a pinch, paying to offset the carbon emissions from their flights. Celebrities face criticism for flying by private jet – and Germany’s Green Party has even put forward plans to ban domestic flights within the country.

Yet according to our calculations based on the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019 (which we both contributed to), CO2 emissions from aviation fuels account for a mere three per cent of global CO2 emissions and eight per cent of worldwide oil consumption. This may not sound like much, but in the past 30 years, aviation fuel consumption has almost doubled, consistently contributing to the growth in global oil consumption.

To see whether the efforts of individuals to cut down on air travel can make a meaningful difference to global emissions, we took a closer look at how fuel consumption by the aviation industry has changed over time, and what trends are set to take hold in the future.

A common way of estimating CO2 emissions for individual passengers is to take the aircraft type and distance travelled into account. This is the method used by carbon offsetting organization atmosfair, and the International Civil Aviation Organization’s carbon footprint calculator.

By contrast, our approach to quantifying CO2 emissions from flights involves looking at the consumption of aviation fuel. This eliminates the need to rely on estimates of passenger numbers, aircraft type and how full or empty planes are, and can easily be compared to other means of transportation.

An important caveat is that our method ignores the effects of condensation trails or nitrogen oxides (NOx) emitted by planes. Including these in the estimates is challenging because their effects only last for a matter of minutes, hours or days. But research suggests that the warming effects of aviation can be much larger, depending on where in the atmosphere NOx are emitted. So our approach only gives a conservative estimate of the emissions from aviation.

The top chart above shows global oil consumption, measured in million tonnes of oil equivalent (mtoe). Over the past 30 years oil consumption has risen continuously, amounting to a 50 per cent increase since 1990. Over the same period consumption of aviation fuel almost doubled from 185 mtoe to 343 mtoe.

Compared to other means of transportation, such as road and rail, aviation accounts for a relatively small but growing percentage of oil consumption. In 2018, aviation was a major driver of the 1.2 per cent global increase in oil consumption.

A large share of aviation fuels are consumed in developed countries. In 2018 the U.S. accounted for more than 20 per cent of aviation fuel consumption. In the same year, half of all aviation fuel consumption took place in OECD countries – a club of mostly developed countries which represent about 15 per cent of world population.

Meanwhile, China, Russia and non-OECD countries in Europe and Asia, which account for almost 60 per cent of world population, consumed 32 per cent of all aviation fuels. Given that the populations of these countries are forecast to grow, we can expect air travel passenger numbers to increase. In fact, the International Air Transport Association estimates that China will replace the U.S. as the biggest aviation market by the mid-2020s.

To put things into perspective, if China, Russia, non-OECD Europe and the rest of Asia were to fly as much as the OECD countries, total aviation fuel consumption would almost triple from its current level of 343 mtoe to about 935 mtoe. It would further increase to 1,560 mtoe, if the entire world flew as much as OECD countries. This amounts to more than the current global consumption of gasoline and diesel.

It’s worth noting that consumption is normally attributed to the country that represents the point of sale: For example, if a Norwegian plane refuels in Iceland en route to the U.S., this counts as Icelandic consumption and emissions. This matters because any attempts by individual countries to tax aviation fuel would be unlikely to succeed, since planes would simply go out of their way to refuel in low-tax countries, meaning a transnational policy is required.

Since 2000, the number of air passengers has almost tripled, reaching a new high of 4.3 billion in 2018. The main driver of growth is budget airlines, which offer primarily short- and medium-haul flights in the American and European markets.

It’s not all bad, though. As shown in the lower left chart, the amount of fuel required per passenger has decreased steadily over the years, although the rate seems to have slowed after 2010, despite the introduction of more fuel-efficient planes. The IPCC estimates that 18 per cent of CO2 emissions from planes can be saved, if air traffic control management and other operational procedures become more efficient.

Based on current information it still seems the increase in passenger numbers is likely to outstrip the increase in fuel efficiency, leading to an increase in overall fuel consumption.

Low-carbon sustainable aviation fuels can reduce CO2 emissions, although only six airports in the world (Bergen, Brisbane, Los Angeles, Oslo, San Francisco and Stockholm) offer them on a regular basis. The International Energy Agency estimates that, in 2018, sustainable aviation fuels only accounted for 0.1 per cent of aviation fuel production.

In 2018, passenger planes emitted around 960m tonnes of CO2, representing 8.5 per cent of emissions from oil products and less than three per cent of CO2 from all fossil fuels – leaving other oil products and coal as the main sources of emissions.

But the fact remains that alternative means of travel, especially trains, have a much better carbon footprint than flying. The London North Eastern Railway estimates that it takes about 17kg of CO2 per passenger to travel from Edinburgh to London, which equates to heating an average UK home for two days. Atmosfair estimates the same journey by plane would produce 145kg of CO2 – equivalent to heating a home for 22 days.

In wealthy nations across the Western world, where people can choose to take alternative transport over short and medium distances at little to no extra cost, “flyskam” may well have its place. But when it comes to tackling climate change, flying less is a small piece in a big puzzle. | W

This article the article was originally published on The Conversation.