Features

Safety

Identifying the problem

The human element is the most flexible, valuable and adaptable part of the aviation system. Such is the description found in CAP 716 created by the U.K.’s Civil Aviation Authority – the governing body that ensures civil aviation standards are set and achieved.

September 26, 2011 By David Olsen

The human element is the most flexible, valuable and adaptable part of the aviation system. Such is the description found in CAP 716 created by the U.K.’s Civil Aviation Authority – the governing body that ensures civil aviation standards are set and achieved. And so if this statement is indeed accurate, it begs the question of why, statistically, have three out of every four accidents resulted from degraded or below optimum human performance?

|

|

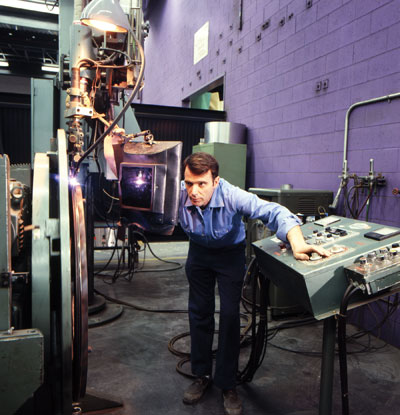

| AMOs work in a hazardous environment and are just as much – or more – at risk from Human Factor conditions as the flight crew. Photo: CCAA

|

Degraded performance can occur anywhere – on the ground or in the air, by anyone involved in the aviation system. This is the Human Factors (HF) variable, a key element in aviation safety defined by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) as being “about people in their working and living environments and their relationship with equipment, procedures and the environment. Just as importantly it is about their relationships with other people.”

Transport Canada (TC) did valuable work on human performance in 1999, introducing HF requirements in CARs for AMOs, airport personnel and Flight Service Specialists (FSS). Transport Canada was very specific about HF training for AMOs; not surprising, since Dr. Bill Johnson, Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Chief Scientific and Technical Advisor for HF in Aircraft Maintenance Systems, confirmed that approximately 80 per cent of maintenance mistakes involve human errors. TC mandated two days of initial HF training for AMOs (Airworthiness Directive B058 4th Ed 2005) but this was subsequently cancelled, a decision QualaTech-Aero Consulting president Keith Green maintains has caused the HF program to stagnate or degrade. QualaTech is an international consultancy group based in Canada that has presented many HF training courses since 2002.

“Some aviation managements are not getting the big picture, in which HF and SMS are key tools to prevent error and financial loss,” says Green. Many view HF training as a cost rather than an investment, he adds.

|

|

| Human Factor elements are felt at every level of the aviation spectrum – from air traffic controllers to AMEs. Here, an on-the-job controller trainee in Gander, Nfld., learns his craft. Photos: NAV CANADA |

Gail Vent shares a similar perspective. The training director of the Canadian Council for Aviation and Aerospace (CCAA) reminds us that the CCAA recognized the importance of HF in the late ’90s, and developed a national two-day human factors certificate course that is TC compliant and includes all aspects of HF and safety management. Vent describes the CCAA’s Human Factors and Safety Management Program as “providing the aviation industry with the information, tools, and training to implement continuing long-term safety programs and procedures which develop and maintain effective human-centered safety management skills and programs.” More than 3,500 people have taken the HF course since 2003 whereas the Human Performance in Aviation Maintenance online training has, since 2004, been taken by more than 5,300 people.

Australian safety researcher Allan Hobbs confirms that QualaTech and CCAA’s concerns are well founded. Says Hobbs: “AMOs work in a hazardous environment that requires physical strength, meticulous attention to detail [and they] may work deep in some confined inner space in extremes of heat and cold and at night.” In today’s stressful world, management and regulators must consider the outcome of employees who may be under marital stress, living in high-cost areas, are having trouble paying a mortgage, and are sleeping badly as a result. All of these situations may be distracting them at work, resulting in a lack of teamwork compounded by a lack of knowledge and training. The end result may be a wide-body jet plunging earthward with 300 people facing oblivion.

There are few true "accidents"

The only true accident is the one that cannot be foreseen, but “accident” is used daily in aviation when it is obvious that most so-called accidents are not true accidents at all. Most are attributed to human error or degraded performance. This demonstrates that we are quick to pass judgment on where and how in the aviation system human failure occurs and have not mastered the art of getting to the “why.” People affected may also suspect that “human error” may be a convenient way of passing blame down to scapegoats at a lower level or those who are dead.

|

|

| Human Factor elements such as distractions at work or poor sleeping habits can seriously affect job performance – and hinder the safety environment. AMOs are particularly at risk. Photos: Air Canada |

For example, after the widely reported case of the air traffic controller falling asleep on the night shift at Washington National Airport on March 23, U.S. FAA administrator Randy Babbitt replied: “As a former airline pilot, I am personally outraged this controller did not meet his responsibility to help land these two airplanes.” A U.S. Republican congressman demanded that the FAA “make an example” of the hapless controller. Stirring words indeed, followed by the suspension of the controller and enforced resignation of the head of U.S. Air Traffic Control.

Given that Babbitt immediately increased nighttime staffing levels and ordered a major system review, cynics might ask why he didn’t initiate these measures sooner and discover why controllers fall asleep. They might also ask why controllers, as reported, take naps while on shift.

|

|

| John David, VP, Safety and Quality, at NAV CANADA, says driving home the Human Factor principles to upper management at various organizations remains a top priority. Photo: NAV CANADA |

While the FAA has been in the news, NAV CANADA has consistently addressed HF with a robust program directed by John David, VP Safety and Quality. David stresses that Human Factors is one of 16 Safety Management Policies forming the core of NAV CANADA’s Safety Management System (SMS). The Policy integrates HF into all activities affecting provision of air navigation services. “The objective,” says David, “is to include HF in the safety and risk management policies, practices and procedures, and to systematically apply HF in management activity, including the planning, design, development, deployment, operation and maintenance associated with NAV CANADA services.”

“HF underpins all elements of the company SMS,” David says. “For example, we use it to investigate aviation incidents, to understand the reason why the event occurred, focusing on identifying organization, local workplace conditions, or changes in the operating environment that may have played a role.” Controllers and FSS are introduced to the basic HF concepts early in training, and annual recurrent training contains HF topics, such as Just Culture, Threat and Error Management, Fatigue Management, and, most recently, the Human Factors of Automation in Air Traffic Management. It also provides the view from the pilot’s world through an overview of HF and Automation in the Cockpit.

Under the microscope

The HF issue of fatigue captured public interest after the high-profile Feb. 12, 2009, Colgan Air crash at Buffalo. Media coverage in the U.S. and Canada pointed to pilot fatigue. But fatigue, while deadly, is just one of the widely recognized “dirty dozen” human factors. Furthermore, HF affects everyone in aviation – flight crew, maintenance engineers, designers, airport staff and AT controllers – throughout the system. It can even include passengers – for example, the intoxicated passenger who caused the fatal crash of a floatplane on the B.C. coast in 2010. The November/December 2010 issue of Wings also highlighted the case of the fatal crash of the MK Airlines Boeing 747 at Halifax in 2004, in which crew fatigue was cited as a major causal factor. Taking the total HF view, however, there was more to it than just fatigue. In this and other incidents, the question remains: why are people fatigued and what were the other HF pressures?

The answer can be found in an analysis of the Pandora’s Box of human factors (the “dirty dozen”) and how they interact. The “dirty dozen”:

- Lack of Communication

- Lack of Knowledge

- Lack of Teamwork

- Lack of Resources

- Lack of Assertiveness

- Lack of Awareness

- Complacency

- Distraction

- Fatigue

- Pressure

- Stress

- Norms

The Colgan crash bears scrutiny in terms of the “dirty dozen.” The NTSB report illustrates that as many as nine were involved and this was only at the flight crew level. Those factors were interacting and some must also have been in-play at other levels in the company organization. If crew members lack knowledge or are under stress – and fatigued – who else may have caused that situation? What human factors were affecting them?

This problem is by no means new, but after an accident, authorities continue to close the stable door after the horse has bolted. The U.S. National Transport Safety Board (NTSB) chair praised the FAA administrator for initiating regulatory changes in response to the Colgan Air crash and regulators worldwide often propose changes after a problem has killed people. We are transfixed by the “how and what” but are not proactive enough about the “why.”

So, how do we learn from these events? Often it seems, it’s too little, too late – as grieving relatives complain. There are certain eerie similarities between the Colgan Air crash and the loss of Air France 447 over the South Atlantic in 2009. In particular, both aircraft stalled, and, in neither case did the pilot(s) level the attitude – the planes remained nose up with high angles of attack. These incidents have generated a huge debate about pilot training, flight deck automation and stall recovery techniques for new-generation aircraft.

At the Flight Safety Foundation safety seminar in Milan last November, FAA HF specialist Dr. Kathy Abbott presented evidence of “disharmony between crews and their automated aircraft.” Unfortunately, as with fatigue, the aviation industry has perhaps had a historical tendency to underestimate the effect of the “dirty dozen” and overestimate the human capability to cope with them. So, it remains to be seen if anyone will act on the “disharmony.” And in case we think we have fixed the problems, consider this: since 2000, some 9,000 people have been killed in more than 340 global airline accidents. And industry observers are concerned that safety improvement has stagnated.

This is the first of a two-part series in Wings dedicated to Human Factors and safety concerns. Part 2 examines the HF effect on the flight crew.