News

Business Aviation

Inside Canada’s proposed Luxury Tax

A Late September deadline approaches for Canadian aviation stakeholders to comment on industry altering costs

September 21, 2021 By Steven Sitcoff

Steven Sitcoff is a tax lawyer specializing in the aviation industry at national law firm McMillan LLP. (Photo: McMillan LLP)

Steven Sitcoff is a tax lawyer specializing in the aviation industry at national law firm McMillan LLP. (Photo: McMillan LLP) The Canadian federal government’s budget announcement on April 19, 2021, included a proposed luxury tax on certain aircraft, cars and boats, to be in effect from January 1, 2022 (the “Luxury Tax”). The Luxury Tax was first introduced as part of the federal Liberal Party’s 2019 election platform. On August 10, 2021, the federal government finally released details of the proposal for consultation.

To begin, let’s address the elephant in the room: This measure is politically, and not fiscally, motivated. Similar to the rhetoric that appears in the budget announcement, the recent release states, “It’s fair today to ask those Canadians who can afford to buy luxury goods to contribute a little more.”

Note, however, that the budget estimated that the Luxury Tax would raise $604 million over a five-year period, whereas federal Covid spending to date exceeds $345 billion. Clearly, if the underlying objective of the Luxury Tax is genuinely to offset Covid spending, it is not the most-effective means of doing so. More ominously, the funds that are anticipated to be raised by the Luxury Tax would almost certainly be outweighed by the adverse economic impact that would follow for jobs and businesses in the aviation industry.

It is proposed that the Luxury Tax would apply with respect to the acquisition of an aircraft meeting all of the following criteria:

- The gross purchase price (i.e. not including the value of any trade-in), including applicable duties, charges and taxes other than GST/HST/PST/QST exceeds $100,000;

- It has a maximum passenger capacity of less than 40 seats;

- It is new, with a date of manufacture after 2018;

- It is not exempt from the Luxury Tax, on the basis of having been either:

(a) Acquired by a qualifying user (e.g. police or fire department, or a municipality), or

(b) Certified to be used “all or substantially all” (generally, 90 per cent or more) in one or more qualifying exempt activities; and - The Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) had not previously issued a certificate which certifies that Luxury Tax had already been paid in respect of that particular aircraft (i.e. the apparent intent is that a particular aircraft should be subject to the Luxury Tax only once).

Among the listed qualifying exempt activities are the following:

- Flights to and from remote, fly-in communities;

- Scheduled service to the general public;

- Air ambulance services;

- Flight training services;

- Cargo services;

- The provision of a charter service where all or substantially all of the seats are offered for sale on an individual basis to individuals who are at arm’s length with the seller.

Whereas the budget announcement referred to “personal” aircraft being subject to the Luxury Tax, the recent proposal no longer makes that distinction and applies equally to corporate-owned aircraft where the use of the aircraft, even if for legitimate business purposes, does not fall within the narrowly defined scope of qualifying exempt activities.

To that end, it is of note that the following would generally not constitute qualifying exempt activities:

- The provision of charter services sold to corporate or other groups, such as sport teams or employees of companies with operations in remote locations (such as in a resource industry); and

- The acquisition of an aircraft by a corporation for purposes of transporting its employees in the course of its business (such as executives of a national retailer who wish to make site visits at its various operating locations).

Triggering events for the application of the Luxury Tax are as follows:

- Acquisitions of aircraft on or after January 1, 2022: Either upon delivery in Canada (in which case the tax is collected by a registered vendor for remittance to the CRA) or upon importation into Canada (in which case the tax would be collected by the CBSA), as the case may be. Deliveries and importations on or after January 1, 2022, would be exempt where made under a written agreement made prior to April 20, 2021.

- A lessor’s acquisition of an aircraft for purposes of leasing it would generally be subject to the Luxury Tax, whereas a lessee should not be subject to the Luxury Tax on the lease.

- Modifications to an aircraft made within 12 months of delivery or importation where the total price paid is $5,000 or more.

- Where there is a change of use whereby an aircraft which was previously certified to be used in a qualifying exempt activity no longer qualifies, the owner must self-assess the tax.

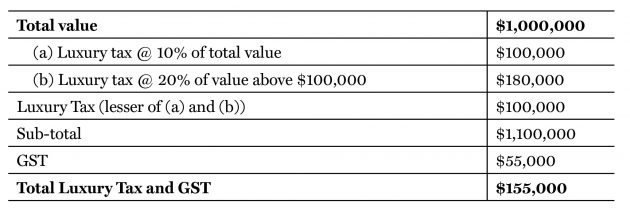

The Luxury Tax is calculated as the lesser of 10 per cent of the total value of the aircraft and 20 per cent of the value above $100,000. As well, the calculation of GST (and presumably PST/QST) would be based on the final sale price, inclusive of any applicable Luxury Tax. (The following chart illustrates the calculation for an imported aircraft valued at $1 million.)

Impact on vendors

The Luxury Tax would be particularly burdensome to vendors such as OEMs and dealers.

First, if a vendor knows, or ought to have known, that a purchaser’s declaration as to being a qualifying user or as to the aircraft being for use in a qualifying exempt activity is false, the vendor would be jointly and severally liable with the purchaser for both the tax and a penalty equal to 50 per cent of the tax. As such, given that vendors could potentially be subject to the tax and penalty even absent actual knowledge on their part of a false declaration, it would be prudent for them to document that they took commercially reasonable measures to make necessary inquiries with the purchaser in order to avoid potential liability.

Next, the Luxury Tax establishes a set of mandatory registration rules which require that most vendors of aircraft that exceed the $100,000 threshold first be registered before the importation or delivery, as the case may be, of any such aircraft is first made. A vendor which does not make a qualifying sale in any 12-month period risks having its registration status revoked by the CRA. The latter is particularly relevant because the registration generally enables the vendor to acquire or import an aircraft for resale without being subject itself to the Luxury Tax.

The registered vendor of an aircraft that is subject to the Luxury Tax is required to remit the tax to the CRA and to provide the CRA with details of the transaction, such as the date of delivery and the aircraft’s unique identification number, in order to obtain a tax-paid certificate. If the tax-paid certificate is not requested within one year of delivery or importation, the vendor is subject to a penalty of $1,000.

Finally, the Luxury Tax establishes a reporting regime not dissimilar to that required for GST purposes. In particular, registrant vendors would be required to file Luxury Tax returns every quarter and to remit any Luxury Tax due for that quarter to the CRA. As well, registrants would be required to maintain records for a six-year period sufficient to indicate compliance with the various rules applicable under the Luxury Tax.

Key takeaways

The Luxury Tax raises several troubling concerns for the aviation industry in particular, including the following:

- It continues the misguided perception of business aircraft as being “luxuries” no different from cars and boats, rather than genuine business tools.

- It would encourage purchasers to buy aircraft from non-Canadian dealers and to register and maintain the aircraft outside Canada while still very much operating point-to-point in Canada. If that occurs, it would have a detrimental impact on the business of Canadian vendors and management companies.

- It would encourage purchasers to buy older aircraft which may not have the same level of safety equipment that is included in newer aircraft.

- It would result in the imposition of an additional and onerous layer of registration and reporting similar to that already applicable under the GST, thus increasing the compliance burden of aircraft vendors.

- It would expose aircraft owners and vendors to an increased level of audit risk as the CRA would seek to verify ongoing compliance with the Luxury Tax regime.

- Most alarmingly, while the Luxury Tax is ostensibly targeted at the supposedly wealthy owners, if enacted it will undoubtedly have a disproportionately harsh impact on the Canadian aviation industry and the high-value jobs and businesses that it represents.

The government has invited written submissions on the Luxury Tax to be sent to fin.luxury-luxe.fin@fin.gc.ca by September 30, 2021. | W

Steven Sitcoff is a tax and aviation lawyer at national law firm McMillan LLP. He can be reached at steven.sitcoff@mcmillan.ca.