Features

Operations

Lawrence of Arabia is on the wing

June 24, 2009 – When the Royal Air Force (RAF) courier interrupted young Harry’s crap

game in London’s Savoy Hotel, the Canadian flier had little reason to

believe he would be alive in a week’s time, let alone finish his game.

June 24, 2009 – When the Royal Air Force (RAF) courier interrupted young Harry’s crap

game in London’s Savoy Hotel, the Canadian flier had little reason to

believe he would be alive in a week’s time, let alone finish his game.

June 24, 2009 By Steve Zoltai

|

|

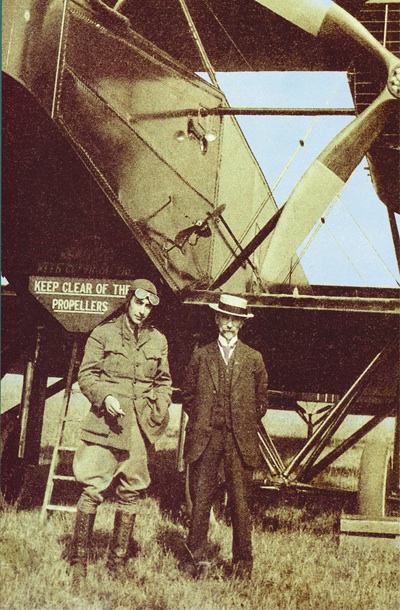

| Young Harry Yates and the Handley Page bomber. Photo courtesy the Yates family |

When the Royal Air Force (RAF) courier interrupted young Harry’s crap

game in London’s Savoy Hotel, the Canadian flier had little reason to

believe he would be alive in a week’s time, let alone finish his game.

Still, Flight Lieut. Harry Yates loved a challenge. Besides, the secret

mission offered an opportunity to settle a personal score and, since he

had only been given six months to live, Harry felt he had little to

lose.

THE MISSION

On June 20, 1919, Harry Yates was in London celebrating his recent

London-Paris multiengine flight record when the courier knocked at his

door. Three hours later, he was flying his Handley Page (HP) bomber to

Lympne near the coast. At dawn the next day, he met a British Foreign

Office agent and was airborne minutes later on a five thousand

kilometre flight to Cairo. The Foreign Office official was Harry St.

John Philby, father of the infamous Cold War era British/Soviet double

agent, Kim Philby. Philby was being dispatched to Cairo to quell Arab

unrest caused by British betrayal of promises of self-determination

made by Lawrence of Arabia in exchange for their resistance against the

Ottoman Turks.1

Harry was to leapfrog his way across Europe and the Mediterranean,

arriving in Cairo in the shortest possible time. The previous

London-Cairo record was 15 1/2days held by an Englishman, RAF Maj.

A.S.C. MacLaren. Air Ministry ground support was promised along the

way.

Harry had very personal reasons to attempt the record. Yates had been

ordered to train MacLaren to fly HPs but had never been told the nature

of the mission which, doubtless, he would have felt perfectly qualified

to do himself. Second, he began to suffer chronic stomach pain while

training in France. Eventually it became so severe that half his

stomach was removed, and the surgeon gave him just six months to live.

Harry was effectively operating under a death sentence.

|

|

| Dr. Harry Yates, DC |

GOING FOR THE RECORD

Guy Simser, a Kanata, Ontario, aviation writer, used Harry’s journal

entries to reconstruct events along each of the 10 stages of the flight

plan. Promised Air Ministry ground support consistently failed to show,

leaving Harry and crew to fuel and maintain the giant bomber themselves

and costing them valuable time. His obstacles illustrate the

rudimentary nature of flight in those days. The landing field in

Marseilles was strewn with boulders which blew out two tires. During a

quick lunch break, their map was stolen. Writes Simser, “With no

direction beams, radar or radio in 1919, maps were essential.

Improvising, they borrowed a local encyclopaedia and traced maps of

southern Europe and the north coast of Africa.”2

Particularly hazardous was the flight taking them over the mountains

across Italy’s boot. For Canadians used to flying over the relatively

sedate landscape of England and northern Europe, the sudden appearance

of mountain peaks and cliff walls was alarming. Harry called it, “the

roughest trip I have had yet,” but would have to revise his statement

the next day. The Greek leg of the route offered no possible landing

sites so when a fuel pump quit with only 15 minutes of fuel, the only

potential landing spot was a partially dry, rocky river bed. The

landing was so dangerous that Harry and his co-pilot shook hands before

making the attempt. Philby, cloistered in the rear cockpit, could only

pray.

Harry successfully landed the giant bomber in the narrow fissure

suffering only a broken tail skid and a punctured tire. Excited locals

cleared a pathway of boulders for take off and helped lift the rear of

the six-ton plane on their shoulders to make repairs.

|

|

| Colonel T.E. Lawrence, a.k.a. Lawrence of Arabia. Photo courtesy the Imperial War Museum |

The

most eventful portion of the journey, however, turned out to be on

arrival in Suda Bay, Crete. Nearing Crete, Harry suspected a cracked

propeller when the bomber began to shimmy alarmingly. The landing strip

was located in an extinct volcano and, when the exhausted pilot came in

too low, Yates very nearly tore a wing off the plane. Examination

confirmed the propeller was unusable, and a new one essential, or the

record attempt was doomed. Serendipity intervened when Harry was able

to cannibalize another stranded RAF bomber of its serviceable

propeller. In the meantime, Philby came across Col. T.E. Lawrence, the

legendary Lawrence of Arabia, who had also become stranded in the

extinct volcano en route to Cairo. Lawrence had slipped away from the

Paris Peace Conference, ostensibly making his way to Cairo to retrieve

his notebooks, which he would later use to write Seven Pillars of

Wisdom, an account of his First World War exploits. With the Foreign

Office secret agent, and now the iconic Lawrence of Arabia, in tow,

Harry had more incentive than ever to deliver his passengers safely and

in record time.

Flying to to Lybia the next day, the crippled HP’s fuel pump failed.

With no life jackets or lifeboats on board, ditching in the

Mediterranean meant certain death but by noon they were over the vast

desert of North Africa. After refuelling, with both crew and aircraft

at breaking point, they pushed on to Cairo. On arrival, they couldn’t

find the airport. The airport was finally spotted by Lawrence who had

bellied out onto the wing to get a better view.

When the tattered HP’s wheels touched down in Cairo on the night of

June 26, Harry had broken the 15 1⁄2-day London-Cairo flying record by

10 1⁄2 days. His new record was five thousand kilometres in 36 hours

flying time, over five days, and would have been better if promised

ground support had materialized.

HARRY YATES, DC

“In the ensuing years”, writes Simser, “Yates’s stomach responded

poorly to medical treatment. Although he outlived, by far, his military

doctor’s prognosis of six months, he found no remedy until he turned to

chiropractic. Indebted, he became a chiropractor.”3

Yates became a major figure in the chiropractic community, serving in

various capacities, including Canadian Chiropractic Association

president and parliamentary representative, president of the Ontario

Chiropractic Association, and member of the Canadian Memorial

Chiropractic College board of governors.4,5 He maintained a lifelong interest in flying, however, and died en route to the Warbirds’ 50th anniversary reunion in 1968. •

REFERENCES:

On descending through cloud cover over Pisa later that day, they

couldn’t find the airport and so, they used the Leaning Tower as a

landmark.

- Pope LS. Another incredible journey. Sentinel, October

1968; reprinted in the Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association

1970 (July);14(2):31. - Simser Guy. A daring young man in his flying machine. The Beaver, 2000 (June/July), 80(3):11.

- Ibid, 15.

- Keating Joseph Jr. Flying chiros. http://drnikel.com/FlyingChirosPartIofII.aspx

- Pope LS. Another incredible journey. Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association 1970 (July);14(2):31.

Steve

Zoltai is the collections development librarian and archivist for CMCC

and was previously the Assistant Executive Director of the Health

Sciences Information Consortium of Toronto. He has worked for several

public and private libraries and with the University of Toronto

Archives. Steve comes by his interest in things historical honestly –

he worked as a field archeologist for the Province of Manitoba. He can

be contacted at

\n szoltai@cmcc.ca.