News

A journey through the clouds

It’s an astounding accomplishment – imagine four generations of Canadian military pilots in one family? There’s the grandfather who took to the air in the First World War, was shot down, wounded and taken prisoner. His son served with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm in the Second World War. His grandson has 40 years between the RCAF and commercial airlines, and today, almost a century later, two great-grandsons carry on the tradition with the RCAF.

September 4, 2015 By Paul Dixon

Charlie Pym and son John Pym in front of C-142 Dash 8 “Gonzo” 402 Squadron. It’s an astounding accomplishment – imagine four generations of Canadian military pilots in one family?

Charlie Pym and son John Pym in front of C-142 Dash 8 “Gonzo” 402 Squadron. It’s an astounding accomplishment – imagine four generations of Canadian military pilots in one family?Guy Pym was 18 in 1912 when he arrived in Canada with his older brother, Ronald. Their late father, Rt. Rev. Walter Ruthven Pym, may have been the Bishop of Bombay at the time of his death in 1908, but as his sixth and seventh children, their future prospects in England were extremely limited. They, and thousands like them, were drawn by the seemingly unlimited opportunities offered by the Canadian west. So, they took up farming on a quarter-section near Mirror, Alta. as the dark clouds of war were gathering over Europe. When war broke out in 1914, Ronald was amongst the first to volunteer, enlisting in the 31st Battalion in Red Deer. Guy stayed on the farm for two more years and then he, too, made the trip to Red Deer to enlist in the 187th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force.

At the outbreak of war in 1914, the Royal Flying Corps comprised seven squadrons made up of a motley assortment of machines. The handful of British and French airmen were opposed by Germans in equally frail machines. The first aerial encounters were little more than exercises in fist-shaking, which led to shooting at each other with service revolvers and hunting rifles. The war wasn’t over by Christmas that first year and as it progressed, tactics and technology improved by leaps and bounds as each side realized the potential that air power would have in determining the outcome.

At some point after the 187th Battalion arrived in England in February, 1917, Pym was offered the opportunity to transfer to the RFC. Second Lieutenant F.G. Pym received his wings on Jan. 21, 1918 and was assigned to the 57th Squadron RFC in northern France. This squadron was equipped with the Airco DH4, the RFC’s first purpose built day bomber. It was a popular aircraft with its pilots, who appreciated its handling, high speed and high rate of climb, which made it very difficult for German fighters to intercept. There was a forward-firing .303 Vickers for the pilot and the observer was equipped with a Lewis Gun.

Through the summer of 1918, 57 Squadron was busy attacking and bombing German positions and airfields. Most days saw crews fly two missions a day. Pym and his observer had four aircraft shot to pieces around them during this time, but managed to get their damaged aircraft back across the lines each time. Their luck finally ran out on Sept. 26, 1918. They were sent up for a third time that day over Cambrai and their flight of four aircraft was jumped by a much larger group of German aircraft.

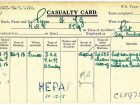

Two of the British planes were immediately shot down in flames. Pym’s aircraft was raked by gunfire, hitting him in the knee, destroying the engine and throwing the aircraft into a spin. Even in an apparent death spiral, German planes pursued him and it was only when he entered a cloud bank that his pursuers broke off. Emerging from the clouds a few hundred feet above the ground, he managed to get the plane under control enough for a dead stick landing. He landed safely, but far behind the German lines. Quickly taken prisoner, the war was over for Lt. Guy Pym as he was to spend the next four months in a POW camp. Pym was listed as “missing” and his fate as a POW wasn’t confirmed until a week after the armistice was signed. He arrived back in England on Dec. 30.

Another generation is born

By the summer of 1919, Ronald and Guy had returned to the farm in Alberta and resumed the life they had left behind. In the early ’20s, Ronald married and left the farm, taking a job with the Canadian National Railway in Toronto. Guy remained on the farm and married Octavia Ruggles-Brise. Their only child, Stephen Guy Pym was born in 1925.

Interviewed in 2014, Stephen recalled his father as “frightfully British. He was a Canadian, but he never lost the little trappings of being an Englishman.” Guy maintained his ties to the military through the cadet movement and Stephen recalls attending cadet camps every summer. When war returned in 1939, Guy Pym was back in the army, but this time he stayed on the ground with the artillery. The farm was sold, with Stephen and his mother moving to West Vancouver. Other than a couple of short encounters, Stephen didn’t see his father again until after the war.

While finishing high school in West Vancouver, Stephen was active in air cadets at the old Stanley Park Armouries in Vancouver. Upon reaching his 18th birthday and graduating from high school, he enlisted in the RCAF and was selected for pilot training. “My first posting was to ITS, Initial Training Service in Edmonton,” he said. “From there, I went back to Abbotsford to Elementary Flying Training School under the Commonwealth Training Program. Then they sent me to Vulcan, Alta. for my service training. That’s where I completed my pilot training and got my wings. After that I went to Three Rivers, Que. to what they called Battle School.”

By this time in late 1944, the Commonwealth Training Program was winding down due to a surplus of trained pilots. One branch that was still actively seeking pilots was the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm and thus Sgt. Pilot Pym, RCAF became Sub-Lieutenant S.G. Pym, Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve. Once in England, he was back in a Harvard at the Advanced Flying Unit, then on to Torrent Hill, Shropshire and the Miles Master. The final stop was at Portsmouth, RNAS Lee-on-Solent for training on Seafires.

Carrier training was conducted on HMS Pretoria Castle, a converted liner with a flight measuring all of 594 feet. The Seafire models in use by 1945 had the more powerful Griffon engine. Unlike the Merlin, the Griffon spun to the right, which induced a powerful tendency for the aircraft to turn suddenly into the carrier’s island on the takeoff roll, yet another challenge for inexperienced pilots. It wasn’t easy, but he made it through just as the war ended.

New aviators are born

Returning to Canada, Stephen reunited with his parents in Grande Prairie, Alta. where Guy Pym had taken a position with the Veterans Land Board. In Grand Prairie, Stephen met and married Florence Bourassa, a union that produced six children and also added another layer of aviator genes. Florence’s older brother was Flight Lieutenant J.M. (Johnny) Bourassa, DFC and Bar, with 55 Pathfinder missions with 635 Squadron RAF to his credit. On his return to Canada after the war, Johnny had headed north and became a bush pilot.

In 1947, he had ferried author Farley Mowat through what is now Nunavut for research that was the foundation for the book People Of The Deer. In 1951, Johnny Bourassa disappeared on a flight from Bathurst Inlet to Yellowknife. Four months after his disappearance, his aircraft was discovered on the shore of a lake far from his intended route, but no trace has ever been found of Johnny Bourassa. Florence’s younger brother, Ray, also served as a pilot in the RCAF during the 1950s and ’60s.

Stephen became a chartered accountant and after spending a couple of years at Port Radium as the accountant for Eldorado Mining, he was offered an opportunity to join an old friend in the lumber business in Abbotsford, B.C. The company had a mill up in Williams Lake and, at that time in B.C., highways were still years in the future. The partners bought a plane for them to fly back and forth, with Stephen filling in as corporate pilot. There were several planes over the years, but his favourite was the Beechcraft Bonanza, with memories of taking his children up when they were very young. Eventually, Stephen moved back to Toronto and stayed there for the rest of his life.

Stephen’s son Charlie remembers that his father would talk a bit about his experiences, but it was difficult to get anything out of him. It was in his later years, when Charlie had established himself as a pilot, that his father was more forthcoming about his RN experiences. “He said as soon as you took off, you were worried about your fuel for landing because there was always a queue to land. There could be a crash on the deck, a plane could land short and crash on the approach to the deck, a plane go off the left side of the deck) into the water, a plane go off the far end into the water and get run over (by the carrier) and or you could crash into the tower.” He was very proud of the Royal Navy and Charlie clearly remembers once making the mistake of referring to the Royal Air Force and being corrected quite forcefully – “it’s the Royal NAVY!!”

Charlie had never considered aviation as a career until one day in the spring of Grade 12, his father came home and asked him if he would like to be a pilot. Stephen had a client whose son was at Royal Military College, training to be a pilot. Father and son looked over the brochure together and it seemed like a good deal. Go to college, learn to fly and then you have a job with the air force when you graduate. That September, Charlie arrived at RMC St. Jean in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Que., which was then a four-year school and his journey began.

“When you sign up they ask you what you want to be,” he recalls. “I said pilot, but so did lots of fellows. We went to Toronto in the fall of our second year for air crew selection and a lot of guys didn’t make it. I was fortunate.”

The next summer he went to Portage for his phase of flight training. There were 13 hours that summer and then back for 14 hours the following summer. He remembers the feeling on passing the second phase of training. “You walk around a little straighter, you’re prouder as a cadet, but you can’t wait to graduate because you’ve had a taste of what your career is and you’re not just a cadet, you are a pilot candidate.” After graduation he was off to Moose Jaw and earned his wings on the Tutor.

Protocol at the time was that if a father had been a military pilot, then he could pin the wings on his son at the ceremony. Charlie pointed out to his course instructor that while his father had been a pilot in the Second World War, his grandfather had flown in the First World War. Could his grandfather perform the deed? The instructor wasn’t sure, but went off and checked the administrative orders and reported that it only applied to fathers, there was no mention of grandfathers.

When the day came, the general called Charlie’s name and then called his father’s name. “My dad got up, went up to the general and took the wings from him. Then he went over to my grandfather and the two of them made their way over to where I stood and my grandfather pinned my wings on me. That was cool. It got a big round of applause and the general didn’t seem to mind.”

A brand new adventure

The next couple of years saw Charlie back in Portage as an instructor, where he met his wife, Doreen. From Portage he moved on to 435 Squadron to fly the C-130 Hercules, from CFB Namao outside Edmonton. Missions varied from Search and Rescue (SAR) to transport missions supporting Canadian and United Nations operations around the world: Europe, Africa, Middle East, and Asia. One of the benefits of being stationed in Edmonton was that Charlie was able to look in on his grandfather, who was still living on his own at the age of 91.

In 1984, an airshow was planned at Namao with the title, “New and Old.” The new was to be the introduction of the CF-18 to local audiences and the old, as envisaged by organizers, was to be Charlie’s grandfather. It took some doing, but the 91-year old Guy Pym was eventually convinced to be interviewed on a popular local Edmonton TV show. Charlie recalls him sitting there in his jacket and tie, thick glasses slightly askew. Initially he wasn’t very talkative, but eventually the interviewer says, “I understand that at one point you were shot down,” to which he looked at the camera, gave a thumbs-up and said “yes, that’s right.”

Pressed for more information about “that fateful day” he responded, “not much to talk about. We had an encounter, we engaged, my observer fell out, took a bullet in the engine, a bullet in my knee, went down through the clouds, dead-sticked it in and was taken prisoner, all very matter of fact. The interviewer was taken aback.

“The Observer fell out?” to which he simply responded, “yes”. (note: Sgt. W.C.E. Mason died on Sept. 26, 1918. He was buried by the Germans in Awoingt churchyard, just south of Cambrai.) The host tried to regain control by commenting on how much he must be looking forward to the air show, to which he responded very vigorously that he wouldn’t be going because he didn’t care for crowds. That was the end of the interview.

By 1987, Charlie was looking outside the air force to expand his horizons and had applied to all the major scheduled and charter carriers in Canada. He got a call from Nationair and almost before he realized it, he had a job. His last day with the air force was April 30 and his first day with the airline was May 1.

After flying the DC-8-61 for two years, he moved up to the 747. One surprise for Charlie was the abbreviated training in the civilian world. “When I trained on the Hercules, I did three months, just to be a co-pilot. Then I went back to the squadron for two years, got the commander course and another two months training to be an aircraft commander. When I went on the 747 for Nationair, they gave me the shortest ground school, two to three weeks at most and then simulator. Six simulator sessions and the seventh was an MOT check-ride. I was done from start to finish in about a month. I’ll never forget the feeling, standing in front of the Air Canada simulator building in Toronto after passing my captain’s check ride. I’m 35, I’m a 747 captain and I haven’t flown the real plane yet.”

Fly the plane he did. Canadians on vacation, summers to Europe and winters headed south to the sunshine. Nationair took on contract work for Garuda Airlines out of Jakarta, which included scheduled service as well as flying charters to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia for Muslims making their pilgrimage to Mecca, known as the hajj.

Nationair went bankrupt in 1993 and Charlie eventually found himself with another charter upstart, Air Club International, again flying the 747 as well as the Airbus 310. Much of his time with Air Club was spent flying the hajj charters again in Indonesia along with charter work for Air India. Air Club lasted until 1998 and then Charlie moved on to Canada 3000.

The events of September 11, 2001 had a well-documented impact on global airline operations and Canada 3000 was one of the first victims, shutting its doors by November 2001. On the move again, Charlie was hired by Westjet, which was less than ideal. After flying wide-bodies around the world as a captain, he was back to flying as a first officer at the starting rate. Opportunity knocked one more time when he got a call from the air force personnel office in Ottawa asking if he would be interested in coming back, as part of an initiative that saw the RCAF looking to re-engage as many as 100 pilots.

Back in the RCAF, after a period working on the ground, Charlie was back in the air with 402 Squadron, flying the CT-142 Dash 8 “Gonzo” as the platform for Air Combat Systems Officer and Airborne Electronic Sensor Operator training flights. Charlie retired in 2014, but before the third generation was on the ground the fourth generation had already taken flight. Captain John Pym, is flying the CC-150 Polaris with 437 Squadron, and his younger brother Alex Pym is a 2015 graduate of Royal Military College, off to Brandon in the fall for the next phase of his training.

Generations of memories

The Pym family’s story spans multiple generations and helps illustrate the sacrifice, courage and bravery all RCAF pilots possess. It’s a remarkable account that connects the passage of time, reminding us of how Canada is united – and has been protected – by the brave pilots who journey through the clouds.