Features

Safety

Establishing a winning formula

Canadian business aviation is in a constant state of flux and while it represents just one element of the aviation framework in this country, solidifying its place in the overall scheme of things can be a challenge.

September 10, 2012 By Stacy Bradshaw

Canadian business aviation is in a constant state of flux and while it represents just one element of the aviation framework in this country, solidifying its place in the overall scheme of things can be a challenge.

|

|

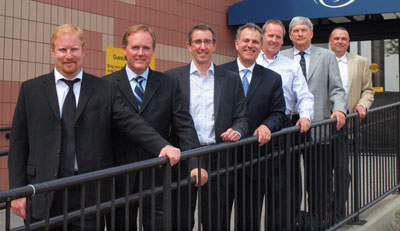

| Participants in Wings’ second annual roundtable from left: Dave Shaver, Director of Business Development, Chartright Air Group; Bill McGoey, President Aurora Jet Partners; Ian Darnley, Director of Business Development, Sunwest Aviation; Sam Barone, President/CEO Canadian Business Aviation Association; Dean Carroll, Director of Flight Operations, Xstrata Nickel; Don Lockard, General Manager, National Socket and Screw; Jamie Vins, President/CEO, Vins Plastic. Photo: Matt Nicholls

|

Business aviation operators are faced with myriad challenges from dealing with economic realities to ongoing human resources issues – and so much more. Determining realistic strategies for successfully meeting these challenges was the impetus behind Wings’ second annual industry roundtable June 14 during the Canadian Business Aviation Association’s AGM and tradeshow in Toronto.

The lively one-and-a-half-hour discussion generated by our super seven panel touched on a variety of key subjects and produced some tangible solutions to these issues. What follows is a snapshot of the discussion.

For more insight, please follow our digital series at www.wingsmagazine.com.

Rolling with the punches

A volatile economy has been a significant issue facing Canadian operators of all sizes over the past couple of years – finding ways to stay profitable and innovative in a challenging environment. We asked panelists how their companies have weathered the storm and what challenges the economic slowdown has created at their firms? Are there any emerging trends or market shifts that are taking place in the Canadian framework?

|

|

| “There will be consolidation as people enter the business and realize it’s not exactly what they thought it was – it’s certainly not as romantic as it would seem from the outside.” – Dave Shaver |

Dave Shaver, director of business development for Toronto-based charter and aircraft management firm Chartright Air Group, said business is once again steady at his firm after marked slowdowns on the charter side in 2008 and 2009. Chartright’s fleet has grown steadily since 2003 when it had five aircraft, and now sits at some 30 fixed wing aircraft including Citation Ultras, Lear 45s, Gulfstreams and Hawker 800s as well as two rotary wing aircraft – an AgustaWestland 119 Koala and an AgustaWestland 109 Grand.

One of the challenges Chartright faces is dealing with a high cost structure due to the flexible nature of the aircraft management and charter business. “We have management agreements that are different – 30, 35 management agreements, each one that’s unique to an aircraft owner or situation. We also have administration that is relatively thorough, and at the other end, we a have a competitive industry that we are in. It’s starting to become fairly generic – and in Toronto with the entry of a lot of brokers from the U.S. as well as Canada, price becomes a very, very strong attribute when customers are considering management or charter.”

Shaver has noticed an emerging trend, indicating steady charter sales, month to month, but it’s quite difficult to predict. There’s also a saturated marketplace where new brokers have entered. “They certainly have a place and represent a spot in the industry, but it’s become very price focused – in combination with the competition out there, it’s become a challenging marketplace to work in.”

Another concern, Shaver noted, has been finding and retaining good people – an issue shared by other roundtable participants. Said Shaver: “Some of the institutions who are releasing people into the business aviation space, we feel some of these people could be given some additional tools. It would help them adjust to the challenges and unique scenarios that we face.”

|

|

| “There’s going to be more industrial charter, more workforce-type transportation as a proportion of the overall business aviation activity because companies are competing to get people, to get them to work sites, to get them in and out.” – Ian Darnley

|

Ian Darnley, director of business development at Sunwest Aviation, has noted a similar increase in competition over the past several months, which he maintains has a tendency to muddy the waters when it comes to quality and price. Operating from bases in Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, and Vancouver, Sunwest is Western Canada’s largest and most diverse business aircraft operator with a fleet of 43 jet and turbo prop aircraft. The company offers a full range of business aviation services, which includes charter, aircraft management, cargo, fractional ownership, aircraft sales and acquisitions and consulting.

“When you talk about the economy, it’s interesting because it’s strong and we have had a fantastic year as well, but it brings all sorts of competition out and that’s fine. We like competition,” Darnley said. “But the interesting thing about our business is there’s a wide variance between quality and pricing. You have people who own aircraft that decide they’re going to become a commercial operator, as opposed to the airline world where pricing is completely consistent and it seems like there’s little consistency in pricing. If you have a good, strong, safe operation with good equipment you expect a certain return for what you are selling – and then someone comes in who’s aircraft is $2,000 an hour less than yours for the same product. That’s what makes it difficult at some times even if the economy is strong.”

|

|

| “The Grand Prairies, the Bonnyvilles of Alberta are boomtowns and we’ve got executives driving three and four hours to their meetings. The same goes for northern Ontario. Infrastructure needs to keep up.” – Bill McGoey |

Bill McGoey, president of the Morningstar Group, made up of Edmonton-based cargo-airline Morningstar Air Express and fractional ownership group Aurora Jet Partners, has navigated a significant corporate restructuring in the shadow of the economic downturn. Morningstar merged with the Ledcor Group and its Opus operation and was rebranded as Aurora Jet Partners. The company has also executed a major move. The Morningstar Group had been based in Edmonton at the City Centre Airport since 1971, but has relocated into its new facility at the Edmonton International Airport as the result of the scheduled closure of the Edmonton City Centre Airport.

Aurora Jet Partners was a spinoff of the Morningstar Group, which has been flying private jets and cabin class pistons turboprops since 1971 in various sizes. The company has also flown Learjets and Cessnas for years, and has six aircraft for its fractional operation with three on order, the first of those three arriving in August including the first Canadian Embraer Phenom 100.

“We started this in 2007, which was not the best time, and of course we hit the cliff in 2009, but it was OK,” McGoey said. “We established with three airplanes, we had an ownership group that was committed to the three, we didn’t lose a customer during that time but we never gained one either [he laughs]. So, the recession was painful. We had growth plans and as you know, the fractional business model absolutely requires scale – you need to get up to that six, eight, 10 aircraft around a nucleus which is currently Alberta and B.C. as quickly as possible in order to minimize expenses such as positioning and so on.

“So, we are at six with three on order which is nine this year and hope to be 20 in the next three or four years. We do see it definitely recovering, the phone is ringing again, and if the economy would just stop getting hiccups we would maybe see some kind of steady improvement here. But overall, we are in a great province, Alberta. As Ian can attest, it’s been fairly well protected in the downturn verses the rest of the country, really the rest of the world, we happen to be the ‘Saudi Arabia’ of Canada. With $100 million invested in the Oil Sands at this time it really helps Calgary and Edmonton. So, this geographic location has helped us.”

Alberta’s oil patch and Canada’s vibrant resource-based economy has helped insulate business aviation during the downturn, notes Sam Barone, president/CEO of the Canadian Business Aviation Association. “When you talk about the economy and what happened in Canada and what happened elsewhere, if you want to go up a little bit to about 40,000 feet, we are pretty tightly fiscally managed in terms of where our economy is and going along,” he said. “Our resource sector, oil and gas, has kept us pretty stable in terms of growth even at a conservative three per cent. But we’re not isolated because of global conditions.

“What we saw in terms of overall trends when the economy took a dip is a lot of Canadian corporations increased their flying. And why? It’s because of the international strategies of a lot of Canadian companies.

They went looking for merger and acquisition targets that were under priced and in some other slowing economies.”

And while many Canadian firms have been very aggressive in international markets seeking out new opportunities, others have been busy reviving their fleets. “When the market went down, prices went down on used inventories of aircraft,” Barone said. “Pricing was probably the best you were going to get. People who had the good credit ratings and cash actually upgraded their fleets that were 20 years old, less fuel-efficient to more fuel-efficient, technically capable aircraft that today have left them better off. So, all was not lost. But I think there’s still a cautiousness that’s become permanent in the economy today and it will continue.”

Does BizAv have an inferiority complex?

Raising the awareness of business aviation in Canada is an ongoing process, and “the Canadian way” seems to be to downplay its role in the overall corporate framework. Why do many Canadian firms fail to acknowledge aviation as one of their necessary financial drivers? Barone was quick to point out it has nothing to do with a lack of aggressiveness in the corporate arena.

“Canada is more conservative, it’s more discreet. It doesn’t mean that we’re not as aggressive globally in terms of doing business, we just have a different perspective in how we do business in this country,” he said.

“The situation in the United States continues to this day in terms of political attacks on the [business aviation] sector . . . starting with the General Motors debacle that started the ball rolling in overall attacks without recognizing the contributions to aerospace, jobs and suppliers – and the aircraft that are used as part of every major economic activity we can imagine.”

It can also be argued, Barone noted, that Canadian companies are generally a lot more conservative in how they manage things publically – it’s not that they’re shying away. “I think in the business aviation community, we all know what it means but we don’t have as open a predisposition if you will about saying, ‘We flew the corporate jet to Vancouver instead of flying on WestJet today.’ Yet, there was a whole level of decision-making that went into that choice as to why that aircraft was used in that way.”

McGoey concurs adding that its almost inherited behaviour. He suggests there’s a big difference between the American and Canadian outlook on business jets. Americans look at corporate jets as a sign of success; they will generally buy the largest jet that they can afford. Canadians, on the other hand, want to buy the smallest jet that will just do the mission in terms of numbers, size and range.

“Americans are a little less conservative in their perceptions of aircraft,” McGoey said. “[President Barrack] Obama hasn’t helped that and he’s suggesting jets are a sign of excess versus success. The bottom line is businesses need private aviation to get to regional offices or where their clients are located. So, clearly [this perception] does need to change.”

|

|

| “I was able to be productive for 162 hours . . . and yes, it’s due to me having a plane. Am I bad for doing it? Well, my factory is still going. I’ll do whatever I need to do to keep it going.” – Don Lockard

|

Don Lockard knows just how critical aviation is to his thread rod manufacturing business. The general manager of Beamsville, Ont.-based National Socket and Screw said his firm’s Cessna Citation Mustang traverses the country moving parts and servicing clients nationwide. “We build our whole business model of what we do on the capability of me being in multiple places almost at once,” said Lockhard. “As the economy goes down, the demands on what I have to do go up . . . and that means I travel. When the economy goes down my travel just goes off the charts and spikes. I will do whatever I can to keep orders going into our shops and keep people busy.”

Lockard flies countless hours per year by himself and notes that he uses a fairly sophisticated spreadsheet to track his whereabouts. Using the aircraft allows him to move around the country and service clients efficiently without wasting valuable in line waiting at congested airports or worse.

“Last year, it was about 162 hours that I was able to stay in the office, one of my several offices, instead of some waiting area some place – or stuck in traffic or in a shuttle to get my bags or whatever. I was able to be productive for 162 hours. That’s a whole month! And yes, it’s due to me having a plane. Am I bad for doing it? Well, my factory is still going. I’ll do whatever I need to do to keep it going.”

Airport Infrastructure – are we doing enough?

Aviation plays a critical role in the Canadian business framework, but panelists agreed not enough is being done to ensure airport infrastructure remains up to snuff. A stronger commitment from various levels of government in providing a more cohesive airport infrastructure would enable more firms to capitalize on potential business opportunities.

|

|

| Raising the bar of Canadian business aviation is a key challenge going forward, according to participants in Wings’ second annual industry roundtable. Photo: Alison de Groot

|

When compared to the airport infrastructure in place south of the border, for example, the Canadian landscape is sorely lacking. Americans, noted McGoey, are very good at building airports and growing their infrastructure, which, in turn, creates significant opportunity for future investment and economic growth.

“There’s something like 15,000 airports in the U.S., about 5,000 of those are paved,” McGoey said. “In Canada, we have about 500 paved airports. You could say we’re only 10 per cent of the American population, so we have the subsequent number of airports, but our landmass is virtually the same size – we both need to cover more than three million square miles of area, so, in theory, we should have a larger aviation sector. It would help as well to have a little more help from the federal government, even on the provincial level, on airports.”

Lengthening runways and ensuring proper safety measures are in place at smaller airports and corporate airstrips are keys to maximizing business opportunities. “The 4,000-foot runways are good for the little pistons and single engines but if you want to sell some jets in Canada and get people moving around at a good pace, we need 5,000-foot runways in any progressive city in Canada,” McGoey said. “The Grand Prairies, the Bonnyvilles of Alberta are boomtowns and we’ve got executives driving three and four hours to their meetings. The same goes for northern Ontario. Infrastructure needs to keep up.”

Barone noted that one of the things the U.S. did right away in the 1960s was to institute programs to fund secondary airports. If you look at major metropolitan areas within the United States, you can see how major centres have secondary options where business aviation is flourishing.

“I think that’s something that’s lacking [in Canada]. One of the problems we face is we have to share corporate aircraft and business aircraft at the large-airline-dominated hubs,” he said. “Toronto is an example, Calgary is an example, Edmonton is an example. And with Airport Authorities being siphoned off from the federal government in terms of management and operation development, we know have more of a hodge-podge development on an individual level instead of a national vision or national aviation policy.”

Working with other associations to establish an effective blueprint that addresses objectives for future airport growth is one of the association’s goals, and will help identify where business aviation fits in the mix. “You know, everyone wants to be across the street here [Barone points to Pearson] – but how do we manage that growth? The city is growing around it, so is there a vision, and who’s doing that? This is something I would like to put on a national agenda across various associations,” he said. “And not everyone is going to see eye-to-eye because Air Canada, WestJet, Transat and Canadian North and the airlines [they have their perspective]. I’ll tell you how many slots they would like to allocate to corporate aviation at Pearson. It’s less than one.”

The impeding closure of smaller municipal airports such as the Edmonton City Centre Airport and Buttonville Municipal Airport in the GTA is also putting significant strain on business aviation. McGoey, for one, fails to comprehend the logic of eliminating such important aviation hubs from the business aviation framework.

“We’re actually shrinking in Edmonton in terms of airports,” he said. “We’re losing our downtown airport.

Many cities in North America and around the world would kill for a downtown airport. Look at the resurgence of the Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport. Business aviation wants to go the heart of a city not out to the regional international airport. And in the case of Edmonton, the Airport Authority, they have to maximize their revenue, so these smaller airports actually bleed off revenue for them, and their preference would be to have one big Taj Mahal rather than one airport that serves commercial airlines and business aviation around it. So, I think the whole regime is problematic to helping business aviation.”

Barone maintains the CBAA tried to present the business aviation case in preventing the closure of both Buttonville and Edmonton City Centre Airport, however the key drivers were the real estate value forces at play that offset any argument of the economic impact from the aviation side of it.

“When you are looking at municipalities that are cash starved and are looking for new sources of revenue [it becomes a challenge], he said. “I think you are right, Matt, the onus is on organizations like ourselves to show the economic value. It’s the same reason why people say, ‘not in my backyard, I don’t like locomotives tooting their own horn’ or they don’t like trucks on the highway. Those trucks on the highway are bringing all the things that you are going to Best Buy for to see on the shelf.

Is Canadian business aviation on the right track?

So, is Canadian business aviation headed in the right direction? Will it continue to be relevant in Ottawa competing with its commercially driven cohorts, or will it continually have its needs curtailed and play “second fiddle” to powerful commercial drivers like Air Canada, WestJet and Air Transat?

Barone is confident the premise of business aviation continues to be relevant today – and will be in the future – simply due to the dynamics of competition and globalization. “And when you take a look at the rationale and the key drivers for business aviation, it’s to maximize first mover advantage in your business – it’s to get to the appointment first, it’s to get that face-to-face time, it’s to get to exploit resources before the other guy does,” he said. “When you take a look at it within the context of competition, both domestically and internationally – and definitely transborder – then that premise and driver is never going to go away. If we are in market-driven economies, aviation will always be a key input in those market-driven economies. That’s relevant today and will be in the future.”

McGoey agrees but cautioned that the industry’s overall success will always be closely tied to the economy, which is fortunately quite stable in this country. “The economy sneezes and our business aviation community could catch a bit of a cold. But the bottom line is Canada’s economy is very stable, we have an excellent banking system and that creates a good, stable environment for business and our businesses are large users of business aviation.”

Darnley joked that while he has yet to find the secret to reading the future, he does maintain market conditions dictate consolidation amongst some commercial operators over the next five to 10 years. “And because Canada’s economy is becoming more of a resource economy, there’s going to be more industrial charter, more workforce-type transportation as a proportion of the overall business aviation activity because companies are competing to get people, to get them to work sites, to get them in and out,” he said. “It’s the service they demand, so you’re going to see that increasing over time as well.”

Shaver added that many who think of jumping into aviation for “romantic” reasons or the allure of quick financial reward may be grossly disappointed. “In the seven years I’ve been with Chartright, the business in Canada has changed quite a bit, certainly more aircraft have entered the market either under management or fractional or in different types of operating structures,” he said. “There’s a certain romance and attraction to aviation with its history and I think it stems from operators and new businesses with the idea that it would be great to start a management company or charter organization because it’s a neat thing or an attractive, romantic business. But when you live and breathe it for some time, you realize it’s a challenging business.

The margins are relatively small, costs can be high due to high flexibility, and variety and the ability to charge a certain price is challenging because there’s a lot of competition.

“As long as the barriers to entry are low, and existing rivalry is high, it will be an interesting business going forward. There will be consolidation as people enter the business and realize it’s not exactly what they thought it was – it’s certainly not as romantic as it would seem from the outside.”