News

Products

Protecting intrepid trailblazers

Entrepreneurial spirit, determination and good old-fashioned guts are all words to describe operators who provide – and have provided – air service in Canada’s north.

May 9, 2012 By Rob Seaman

Entrepreneurial spirit, determination and good old-fashioned guts are all words to describe operators who provide – and have provided – air service in Canada’s north. Names like Wop May, Punch Dickins, George Gorman, Max Ward, William Munroe Archibald, John Austin and Harry Kennedy, among others, bring to mind developing and pioneering air service to otherwise poorly accessible regions of this vast nation.

|

|

| Avidyne’s TAS 600 Traffic Advisory System series can be used with a wide range of aircraft. Photo: Avidyne

|

For a large portion of Canada, air service is by and large the primary means of service and connection with the rest of civilization. For many communities, everything from mail to food, water, fuel, medical supplies – even manufacturing support – is delivered or moved point to point by some sort of air service.

By the 1960s and early ’70s, remote flying was an established and growing service but still somewhat rustic in comparison to today. Jim Morrison is well known to many in the aviation world. Although today he is the managing director of Toronto-based Partner Jet Inc., Morrison earned his way up the aviation ladder through a succession of jobs – starting with flying on the unimproved, underserviced and high-demand routes of the day in the North.

“I spent the very first years of my career working for Russ Bradley at Bradley Air Services based in Carp, Ont.,” says Morrison. After flying aerial surveys on Beech 18s, Aero Commanders and DC3s across North and South America and Africa, Morrison headed to northern Quebec and flew first for Survair and then Air Inuit.

|

|

| TCAS II works by interrogating the ATC transponders of other nearby aircraft to determine and display their altitudes, ranges and relative positions. Photo: Rockwell Collins

|

“We ran a scheduled charter service in those days with Twin Otters, DC3 and Canso aircraft,” he says. “The scheduled flights happened six days a week typically. The run started in Fort Chimo (now Kuujuac), covered Payne Bay Koartak, Wakenham Bay and Sugluc with stops in Leaf Bay and Aupaluk. All of these communities have new names now. The airstrips in the ’70s were anywhere from 800-feet to 1,200-feet, gravel with only NBD (non-directional beacon) approaches and limited weather information along the coast. We would fly the schedule with either the Twin Otter or the DC3 and be on call for medevacs through the nights.

Morrison notes that cargo work was steady, too. The freight loads needed to be moved as well as the mail and fresh groceries. Charters came up on a regular basis and medevacs happened at least four or five times a week mostly late a night and often in inclement weather.

“Turnover was high,” he says. “Pilots typically flew in the north to build hours and move on to the airlines. The average age of pilots up north was roughly 35 and the majority were in their mid-20s as I was. For training, we did an in-house course on the Twin Otters, DC3s but the HS748s were done at Eastern Provincial Airways (EPA).

EPA was the first formal training I saw in the early years and it was exceptional. There was no pressure put on pilots to perform, but it was very competitive. There was a lot of pride in completing flights and getting the job done. Each pilot had his or her own set of limitations and stayed within them carefully. The accidents we saw while flying up there mainly were the result of inexperience or lack of cockpit resource management.”

The changing climate

In speaking with northern-based pilots and operators today, it seems that although the work is basically the same and attracts the same type of aviation crew, the flying hardware has changed and runways are now longer – and flight ops are supported by broader reaching navigational aids. Some northern operators have, at their own expense, implemented on-site improvements at some strips, including lighting and radios complete with locally trained residents to operate and provide real-time observations of local conditions.

|

|

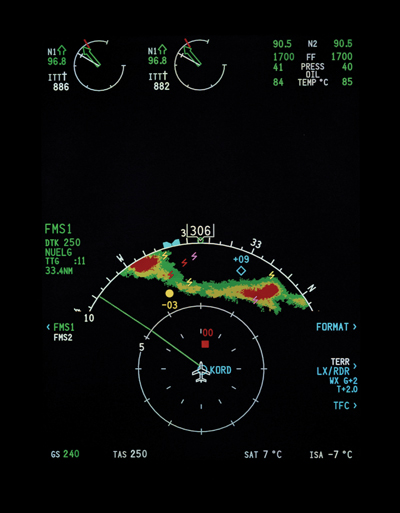

| The Pro Line 21 avionics suite integrates different functions including TAWS and EVS. Photo: Rockwell Collins

|

Technology is also dramatically improved providing operators with new levels of insight. The introduction of enhanced avionics technologies has allowed for vastly improved levels of safety in these operational models. And although many operators have yet to implement some of this technology, chances are, that is about to change.

Incidents such as the flight into terrain accident involving Keystone Air at Spirit Lake in January, underscore the need for advanced technologies in remote locations. They also bring into question issues relating to single-pilot commercial operations, the challenges of working from unimproved local airstrips and the use of newer technology in the cockpit to aid pilot operations. The use and application of Safety Management Systems (SMS) has also been under the microscope.

Transport Canada (TC) was also already in the process of changing some of the requirements relating to aircraft commonly used in this sort of northern flight operation. What Spirit Lake – and other incidents over the past 18 months – did was simply highlight an issue that has been smouldering for quite some time.

New frontiers

Ask anyone in the avionics world and they will confirm that 2012 is indeed a watershed year for Canadian aviation. TC has now published its Advisory Circular AC 600-003 for Terrain Awareness System (TAWS) regulations. As they report, from 1977 to 2009, 35 airworthy aircraft were flown into the ground while under pilot control. Known as controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) accidents, the reported numbers show 100 fatalities and 46 serious injuries as a result of these CFITs. As the circular states: “To date, risk information alone has not motivated all of the Canadian aviation industry to voluntarily equip key passenger aircraft with existing technologies that would help mitigate risks associated to CFITs.”

The current proposed regulatory amendment (as of writing this article) will introduce requirements for the installation of TAWS equipped with an Enhanced Altitude Accuracy (EAA) function in private turbine-powered aircraft configured with six or more passenger seats, excluding pilot seats, and in commercial aircraft configured with six or more passenger seats, excluding pilot seats.

The Gazette states that operators will have two years from the date on which the regulations come into effect to equip their aircraft with TAWS and five years to equip with EAA. “This is a positive change in real terms in safety of flight for remote operations,” says Norm Matheis, Universal Avionics regional manager for Canada. “Our top Canadian Universal dealers are seeing an upswing in hangar bookings now for TAWS mods, in anticipation of the publishing of the TAWS rule in Canada Gazette II this year.”

A TAWS Class A system provides the highest level of protection for operators. It will be required in Commuter CAR 704 aircraft configured with 10 or more passenger seats, excluding pilot seats, and in all aircraft operating under subpart 705 for airline operations.

The Class B system has less capability and will be required for private turbine-powered aircraft configured with six or more seats, excluding pilot and co-pilot. It will also be mandatory on all commercial subpart 703 air taxi aircraft configured with six or more passenger seats, as well as Commuter subpart 704 aircraft configured with six to nine passenger seats, excluding pilot and co-pilot.

Matheis has plenty of experience in northern flight ops. His firm is a pioneer in introducing the WAAS system on aircraft across the country, specifically those flying in northern operations. In looking at northern flight ops safety as a whole, he notes: “Today, we still see some operators in the north operating without CFIT protection apart from their flight crew using MK I eyeball. Some of these aircraft are not even equipped with legacy Ground Prox,” he says. “What is a bit puzzling, is that some of these same aircraft are, however, fitted with TCAS at a hardware cost approximately three times that of TAWS.”

TCAS monitors the airspace around an aircraft for other aircraft equipped with a transponder, independent of air traffic control, and warns pilots of the presence of other transponder-equipped aircraft that may present a threat of mid-air collision. It’s well documented that, as a pilot, you have 10 to 100 times the probability of flying into the ground unexpectedly than you do of hitting another aircraft in mid-air. That’s a sobering fact. And, the problem with traffic collision avoidance system (with no GPWS or TAWS), is the possibility that a recommended avoidance manoeuvre might direct the crew to descend toward terrain below a safe altitude. Requirements for the incorporation of TAWS ground proximity warning mitigates this risk. TAWS ground proximity warning alerts have priority in the cockpit over TCAS alerts (windshear alerting has the highest priority, if so equipped).

According to Matheis, classic GPWS that have provided a last line of defence from a CFIT incident have been available for well over 35 years. Don Bateman, a Canadian-born engineer, developed and is credited with the invention of GPWS. Since 1974, when the U.S. Federal Aviation Adminstration (FAA) made it a requirement for large aircraft to carry ground prox, there has not been a single passenger fatality in a CFIT crash by a large jet in U.S. airspace.

“Universal TAWS with its unique Terrain Awareness modes in addition to standard GPWS modes, has been available since 2000. TAWS will provide crews with a warning of terrain ahead of the aircraft as well as classic GPWS warnings,” he says.

Universal TAWS was also designed to complement well-known Universal UNS-1 WAAS Flight Management Systems (wFMS). Integration with the FMS provides an additional unique predictive alerting feature of Universal TAWS, based on knowing where the aircraft will be later in the flight plan. Universal TAWS uses aircraft inputs such as position, attitude, air speed and glideslope, along with internal terrain and airport databases, to predict a potential conflict between the aircraft’s future flight path and terrain.

The resulting unprecedented look-ahead capability can provide warnings and alerts well in advance of potential hazards, allowing time for the pilot to make the necessary manoeuvres or data corrections for terrain avoidance. UNS-1 FMS also supports true track navigation in northern domestic airspace and has gravel runways loaded in the navigation database. The equal time point/point of no return pages of UNS-1 specifically benefit northern Canada remote ops.

Matheis is far from alone when it comes to offering qualified analysis relating to CFIT incidents and their prevention. According to Field Aviation’s Frank Dennis, there are many affordable navigational options for operators big and small who are looking to improve safety. “They can do so by providing their flight crews with additional tools in the cockpit,” he says.

As an example, Garmin’s new GTN Series of standalone GPS units and GPS/Nav/Com units come standard with high-resolution terrain graphics and WAAS capabilities. Full TAWS-B capability is an option and graphical weather and traffic upgrades are also available. This allows operators to determine which features are most important to their specific operations and to add other features as budget and other operational considerations allow.

Dennis also points to Avidyne’s TAS 600 Traffic Advisory System series that can be used with a wide range of aircraft. The units are compatible with many different manufacturer’s displays, meaning operators may not need to upgrade cockpit displays to add this capability. And as Dennis notes, these systems can be purchased for under $30,000 installed, depending on which add-ons (traffic, weather, etc.) operators choose to purchase.

“With mandatory TAWS regulations coming into force soon, now is an excellent time for operators to research what options are available to them,” he says.

Collins Radio, now Rockwell Collins, has been manufacturing and selling radio equipment since the early 1930s. Rockwell Collins Commercial System products are available for a broad spectrum of aircraft, from communication, navigation and surveillance equipment in turbo prop aircraft, to its Pro Line Fusion system used in intercontinental corporate jet aircraft.

Says John Peterson, director of avionics marketing for Rockwell Collins: “We do have cost-effective solutions for making light business/commercial air travel safer in remote areas. Rockwell Collins offers services and products that can assist pilots and operators in these operating areas, from training and airborne warning systems, to complete cockpit upgrades that take advantage of the latest technologies.”

|

|

| With unique environmental and geographical challenges, Canada’s northern operators are very much in need of cutting-edge navigational tools. Photo: Wilson Aircraft/Cessna

|

One example Peterson highlights is the Rockwell Collins ALT-1000 (radar altimeter). It measures height above terrain up to 2,500 feet and is accurate to within two feet at the critical low altitudes. The instrument provides a second altitude check for a pilot, by giving absolute altitude from the ground as well as providing information for alerting functions, such as DH. “It’s robust and is certified for Category II landings,” he says.

Rockwell Collins’ TCAS system is another option for a modern cockpit. “TCAS II works by interrogating the ATC transponders of other nearby aircraft, to determine and display their altitudes, ranges and relative positions,” says Peterson. “If necessary, they compute and display a recommended vertical avoidance manoeuvre to ensure safe separation. Rockwell Collins, in conjunction with Bristow Helicopters, now offers a turnkey package to install and certify TCAS II on rotary-wing platforms.”

The Rockwell Collins Pro Line 21 avionics suite is another popular unit – and it is no stranger to Canadian skies. The system integrates different functions, including TAWS and EVS. According to Peterson, the Pro Line 21 offers cost-effective EVS solutions that can prove invaluable during dark-hole approaches, dark taxi, and low visibility conditions.

In terms of the future, Peterson points to the Rockwell Collins HGS-3500 (Head-up Guidance System) solution for turboprops and light jets. “This will further improve flight operations by keeping a pilot’s eyes forward and outside the aircraft with synthetic vision, EVS and flight guidance cues.”

Providing a safe working environment

While northern flight operators are indeed subjected to unique flying conditions, there are products out there that can provide a safer flying environment. And although cost may be a concern, many avionics manufacturers will find ways to work with the operators to provide incentives and financing options for those that qualify. With the pending rule changes from Transport Canada looming, the time is now for northern operators to find ways to meet the new criteria – and enhance the safety and quality of their invaluable operations.