Features

History

100 years on, Prince Rupert still remembered for role in first world flight

April 12, 2024 By Seth Forward, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, Prince Rupert Northern View

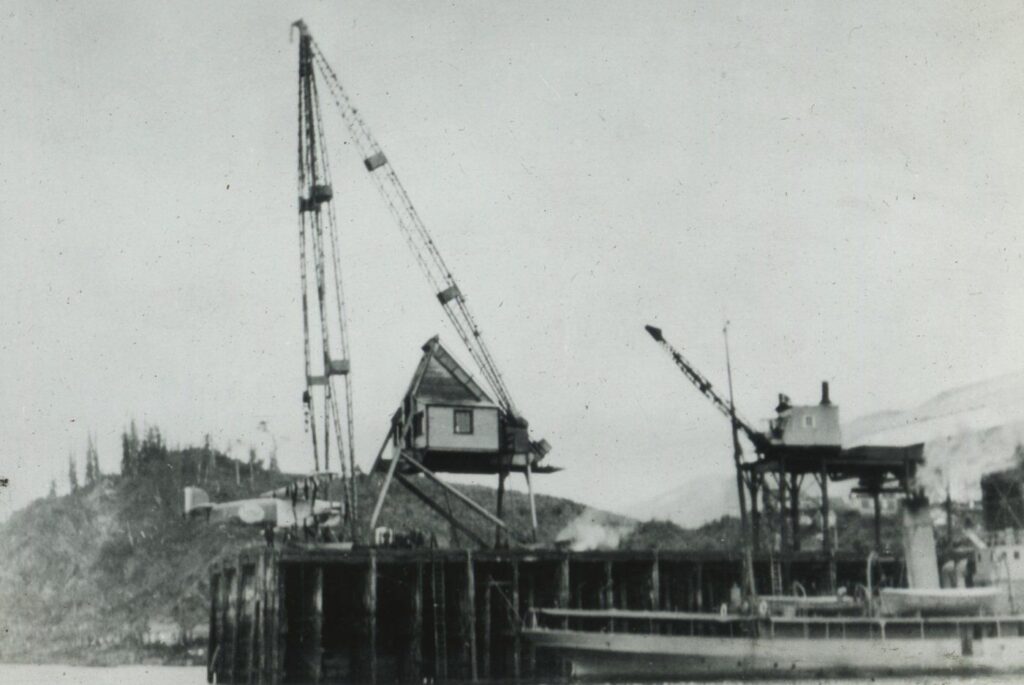

View of one of the Douglas World Cruiser (DWC) aircraft being hoisted out of the water for repairs at Prince Rupert, British Columbia, April 7, 1924. (Contributed by Friends of Magnuson Park/likely US Army Air Service)

View of one of the Douglas World Cruiser (DWC) aircraft being hoisted out of the water for repairs at Prince Rupert, British Columbia, April 7, 1924. (Contributed by Friends of Magnuson Park/likely US Army Air Service) Four U.S. Army airplanes arrived in Prince Rupert on April 6, 1924 – their first stop in what was the first-ever flight around the world, a historic 175-day journey crossing the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic Oceans.

The four planes named Chicago, Seattle, Boston and New Orleans took off from Seattle with eight pilots and mechanics, attempting a daunting global journey that had never been done before.

On the first day of 175 to complete the journey, the pilots were greeted with warm North Coast hospitality, but stormy, freezing weather. The Seattle crashed into the ocean during the perilous storm, miraculously making it to Prince Rupert, where the plane would be fixed with “the finest spruce in the world” in a Seal Cove shipyard.

“Blinded by a snowstorm, Major Martin and Sergeant Harvey in the Seattle nearly ended their flight right then and there,” pilot Leslie Arnold wrote in his trip diary, which would be sourced by author Lowell Thomas for First World Flight, the definitive book on the historic adventure.

“The Seattle side-slipped, fell thirty feet, and dug the left pontoon into the sea. Imagine four tons of airplane crashing that distance into the water! The impact broke the outer struts on the left side and snapped three vertical wires. At that, they were mighty lucky.”

When the four planes came into Prince Rupert, Arnold said they were welcomed by Sam Newton, the mayor at the time.

“‘Gentlemen,’ said the Mayor S.M. Newton of Prince Rupert, as he stood there in the snow looking like Santa Claus, ‘you have arrived on the worst day in ten years!’” Arnold said.

“Sometimes we were flying through driving rain, sometimes through fleecy snow, again through sheets of sleet, and twice through squalls of hail that pelted the fuselage and wings like a flock of machinegun bullets all striking at once.”

Elisa Law, executive director of the Friends of Magnuson Park and organizer of the First World Flight Centennial celebration in Seattle, said that while there was plenty of support for the planes through the U.S. Navy, local help was appreciated as speed was a main priority for the mission.

“There were 36 Navy destroyers all positioned strategically all around the world,” Law told The Northern View.

“So they had a lot of support. It’s not like they wouldn’t have been able to repair that plane with their own resources eventually, but this was a race.”

While the pilots received souvenirs from around the globe, they closely guarded the Union Jack flags given to them by Newton, which can now be found at the Museum of History and Industry in Seattle.

“At the close of the banquet, we were presented with small Union Jacks as souvenirs, and, although we had never contemplated carrying the flags of any other countries, we were treated with such charming hospitality in Prince Rupert that some of us kept these Union Jacks in our planes in memory of the place whose citizens had welcomed us so warmly,” read Arnold’s diary.

The ambitious journey was a major statement to other global powers from the Americans following the First World War.

Two Brits crossed the Atlantic via plane in 1919, while multiple countries failed in their attempts to traverse the world by plane before the Americans were successful.

Law said the first world flight was comparable to the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969 – both incredible feats of innovation that changed the world forever.

Of course, flight technology has evolved dramatically over the last 100 years, and Law explained that the airplanes’ daring pilots – who flew in open-air cockpits with no radios or parachutes – risked their lives every time they entered their planes.

The “fragile” planes were made of wood, cloth and wire, according to Law.

“These men are crazy…like this is a suicide mission,” Law said.

“They’re brave. All the flyers from that era were hailed as heroes. And most of them never had children because they knew that they were taking their life in their hands every time they got in one of those airplanes.”

Pilots of the Seattle Major Frederick Martin and Sgt. Alva Harvey crashed into a mountain in the Alaska Peninsula days after leaving Prince Rupert, having to survive 10 days in the wilderness before being rescued.

The arrival of the airplanes was a monumental event in a time when many had never seen an airplane before.

“Most people thought it was impossible and also most people at this time in history had never seen an airplane…this is the first time an airplane had gone up from America into Alaska,” she said.

“Everywhere they landed, they were treated like heroes.

“All the canneries in Canada and Alaska were shooting off their steam and bell whistles.”

Law also said the trip revolutionized the commercial flight industry, which was essentially non-existent 100 years ago.

”This was the paving of the way of commercial air travel,” she said.

“The route that they took in many cases is still being used by air travel today.”

Three planes made it to Japan, becoming the first to traverse the Atlantic, while only two of the four airplanes completed the journey home to Seattle, where they arrived on Sept. 4, 1924, greeted by 50,000 enthusiasts.

For Law, the centennial is an opportunity to look back at an incredible piece of global history that happened to feature Prince Rupert.

“Prince Rupert was the first stop in the first world flight. That’s a really cool sound bite.”