Features

Operations

Trailblazing the Airways

May 4, 2009 – Whoever said chicks couldn’t fly did not know the story of this plucky little bird from southwestern Ontario.

May 4, 2009 – Whoever said chicks couldn’t fly did not know the story of this plucky little bird from southwestern Ontario.

May 4, 2009 By Kelly Putter

|

|

| Eileen Vollick in her flight suit |

May 4, 2009 – Whoever said chicks couldn’t fly did not know the story of this plucky little bird from southwestern Ontario. Eileen Vollick was just 19 when she earned her wings and the right to call herself a true Canadian pioneer, trailblazing the airways for thousands of women who came after her.

“This woman is a legitimate Canadian hero,” says Paul Kastner, a member of the organizing committee that posthumously honored Eileen recently on the centenary of her birth. “I sort of fell in love with her when researching her background for our event.”

Born in Wiarton, Ont., it was Hamilton that would help nurture Eileen’s great-big imagination. The city was in the throes of a growth spurt during the 1920s that would see new buildings, schools and sporting events dot heighten its sense of civic pride. Eileen’s spirit was very much in keeping with the Roaring Twenties. The spunky and determined teenager took her cues from her independent-thinking mother, a freelance writer and actress set on raising her six children alone while her husband worked as a marine engineer in South America.

“Eileen was very vivacious and everybody loved her,” recalls Audrey Hopkin, Eileen’s 91-year-old sister, from her home in Charlottesville, Va. “Eileen was full of spirit. She could play the piano. She loved parties, when we would all gather round and sing. Our mother allowed us freedom of expression.”

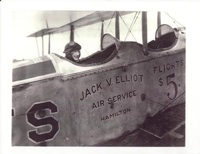

While that freedom meant an easel, art supplies and a room of Hopkin’s own in which to paint, her soon-to-be airborne sister was equally supported in her quest to become Canada’s first licensed woman pilot. The notion gathered wings as Eileen watched from her bedroom window overlooking Hamilton Bay the building of the aerodrome for Jack Elliott’s Air Service.

|

First though, the 18-year-old had an obstacle to overcome – her age. After inquiring if a “girl could fly,” Eileen was given permission by the federal government provided she waited till she was 19. Men could then get their pilot’s licence at 17. But that didn’t deter Eileen.

“Each day as I drove my car past the aerodrome a small, still voice whispered, ‘Go ahead, brave the lion in his den and make known your proposition to him’,“ Eileen wrote in the Canadian Air Review in June 1928, three months after earning her licence. “ I proposed to learn to fly, and fearful of being turned down or laughed at (women had not then entered into this man’s game in Canada) I hesitated wondering how much courage or talent was required to fly an airplane.”

Soon the pretty and petite Eileen was wearing a “cut down” version of one of her father’s mechanic’s suits that her mother had altered, and standing shoulder-to-shoulder with a classroom of 35 male cadets at the Elliott Air Service. On weekends a number of the cadets would wend their way to Eileen’s house, bearing hangovers and looking for Mrs. Vollick’s cure which comprised hot tea and epsom salts. “It would clean out their system and they would feel alright again,” said Hopkin. “Eileen could have a flock of young men after her, but they didn’t pressure her. All those men at the airport were very respectful.”

Eileen took to the air immedately; her first flight was the acid test of her mettle as the pilot manoeuvred the plane into spins, loops and zooms – all designed, she thought, to either frighten her or test her courage.

“As I sat in the cockpit I felt quite at home,” wrote Eileen, who worked as a textile designer at the Hamilton Cotton Company; “fear never entered my head and when I saw the earth recede as the winged monster roared and soared skyward, and the familiar scenes below became a vast panorama of checkerboarded fields, neatly arranged toy houses, and silvery threads of streams, the pure joy of it, gave me a thrill which is known only to the airman who wings his way among the fleecy clouds.”

But before the seemingly fearless teenager earned her wings, she would accomplish another first as the first Canadian “girl” to parachute from a plane into water. Testing her nerve and surely her family’s as they watched her stunt from their Beach Boulevard home, Eileen jumped from the wing of a plane into the Hamilton Bay from an altitude of 2,800 feet.

|

“My mother was frantic because the boat was not there to pick Eileen up,” recalls sister Hopkin. “Eileen loosened the harness and let her parachute drop and swam to the boat as it sped up to meet her. My mother’s language was nothing I’d repeat because she was very upset.”

Memories of Eileen’s jump would linger when Eileen was later asked to parachute into the lake during the Canadian National Exhibition. Her mother said no.

Eileen’s history-making flight would take place on March 13, 1928 when at 19 she flew a ski-equipped Curtiss Jenny from the frozen waters of Burlington Bay, making three three-point landings on the ice and passing her federal test to become the 77th licensed pilot in all of Canada. On that day, Eileen earned her wings with only ten of the male students she had started out with. Because she was barely five-feet tall she would require extra seat cushions to prop her up to seethrough the aircraft’s windscreen.

Aeronautical adventures ensued as Eileen performed aerobatic flying across North America, garnering the attention of famed aviatrix Amelia Earhart, who invited her to join her on a flying tour that would also include Jacqueline Cochran.

“They called it off for some reason,” says Hopkin. “But when we went to visit (Amelia Earhart) in Jackson Heights, Long Island, Eileen asked if I wanted to come up and visit and I said no. I was a teenager and I didn’t want to sit around with the ladies talking.”

Eileen would put her flying career on hold after marrying James Hopkin, a steamfitter from New York State. She would move to Elmhurst, N.Y. and go on to raise two daughters, Joyce Miles and Eileen Barnes.

Eileen has been awarded numerous honours over the years, including the Amelia Earhart medallion in 1975. The most recent award took place in August 2008, when about 250 people gathered to mark her contribution to aviation on the 100th anniversary of her birth in Wiarton. Eileen was feted with the unveiling of a Canada Post stamp and the naming of an airport terminal after her.

During the festivities, Eileen also earned the distinction of being the first and only female in Canada to have a facility named in her honour, when the Wiarton-Keppel International Airport named its two-storey passenger terminal after her. An Ontario Heritage quarry stone recognizing Eileen’s accomplishments was also dedicated on Aug. 2 in the newly-created Eileen Vollick Parkette at Wiarton airport.

The first Canadian woman to pilot a military jet, Maj Dee Brasseur, attended the ceremony, as did a large number of female pilots.

“It’s important that people know that a lot of Canadian women have done some pretty extraordinary things,” says Marilyn Dickson, a member of an international women pilot’s organization that was instrumental in getting Eileen recognized. “It’s important that young people know some of the history, especially our Canadian history.”

Although Eileen died in 1968 at age 60, her flying spirit lives on. Last year, daughter Joyce Miles decided she would celebrate her 76th birthday by parachuting from 10,000 feet with her son and granddaughter. And in Wiarton last summer, sister Audrey Hopkin, who celebrated her 90th birthday by bungee jumping, took her first flying lesson at the age of 91 with Marilyn Dickson.

“She took the controls to fly across the Bruce Peninsula,” says Dickson of her oldest student ever. “Later she said she understood what her sister got so charged up about for all those years she was flying.”