News

Glidepath: Honouring true professionals

A few years ago, I was walking through the West Vancouver Cemetery, reading headstones as my companions payed their respects to long-departed family members. For the most part, the cemeteries here are very egalitarian, simply rows of flat markers with little to differentiate them.

November 3, 2016 By Paul Dixon

“consider the people who made it work and got those trainees where they needed to be.” A few years ago

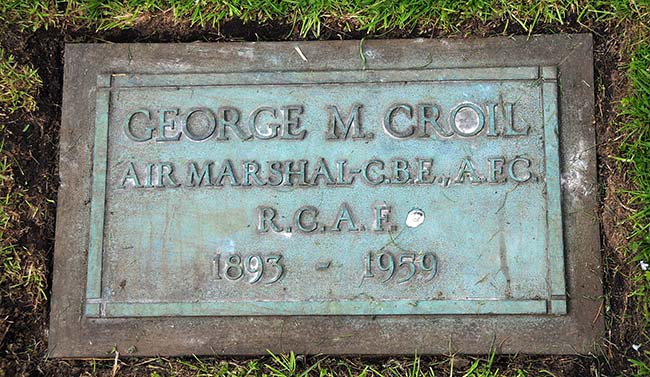

“consider the people who made it work and got those trainees where they needed to be.” A few years agoWhat caught my eye in this particular section were the number of MM (Military Medal) and MC (Military Cross) designations, veterans of the Great War. In the middle of these countless rows of markers, I came upon one that stopped me in my tracks. It simply read George M. Croil: Air Marshall – CBE, AFC. RCAF. 1893 – 1959.

At that point, I had never heard of Croil. I knew about Bishop, Barker and Brown from the Great War, but Croil meant nothing. I was able to find information online, but there’s not a lot. A long story made short, Croil is credited with creating the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in the years leading up to the Second World War. Born in Milwaukee and raised in Montreal, he was employed as a tea planter in Ceylon when the First World War broke out. Immediately returning to Great Britain, he enlisted in the Gordon Highlanders as an infantry officer, before transferring to the Royal Flying Corps in 1916. He served as a flying instructor in the Middle East until 1919 and, for a brief period, served as the personal pilot of a certain Major T.E. Lawrence, perhaps better known as Lawrence of Arabia.

Earlier this year, when I talked with Ricardo Traven and Justin Carlson of Boeing’s Super Hornet team, we talked about the mistake that so many people make. They were referring to fighter aircraft, but this is true of so many things in life – “amateurs talk tactics and professionals talk logistics.”

George Croil was a professional, a consummate professional. In 1920, he had returned to Canada and was appointed to the Canadian Air Board. In 1924, when the RCAF came into being, he was one of the 62 officers that comprised the officer corps. By 1935, Croil had risen to the rank of Air Commodore, followed in 1938 by promotion to Air Vice Marshall, reporting directly to the Minister of Defence (over the protestations of the Army, which up to now had controlled the air force).

As war clouds were forming over Europe, Croil was instrumental in laying the groundwork (with the meagre resources available) for an air force that would total 78 squadrons by wars end. In 1940, he displayed what might be termed the ultimate act of a professional when he was asked to step aside as chief of the air staff. The air minister felt he needed someone in the position who would share the minister’s appreciation of the social niceties, whereas Croil was seen as having a puritanical streak, not to mention an oversized work ethic. He did resign, serving out the next four years as inspector-general of the RCAF.

Tactics versus logistics. We are dazzled by the bright shiny things that go fast and make a lot of noise. These things are great and are generally at the pointy end of the stick, but all too often, there is no thought given to what it takes to get those things, keep them running, not to mention what’s involved in the care and feeding of the human side of the equation.

Look at the role Canada played in the logistical side of the Second World War – the North Atlantic convoys for example. Think about what it took to organize the cargoes that went into those ships that sailed for Britain or north to Russia. Or by train, from all over Canada and the U.S. to the ports, over the same tracks as the trains carrying tens of thousands of military personnel every day. Someone had to organize this and keep it running smoothly.

In the beginning, the RAF said it couldn’t be done. Lord Beaverbrook (a Canadian) took on the job and proved it could be done. Consider the British Commonwealth air training plan and what it took to train more than 130,000 personnel at more than 130 training centres across Canada, with moves to different training centres for different phases of their training. There were no computers and even the telephone network was rudimentary. Consider the people who made it work and got those trainees where they needed to be when they needed to be there and got them headed overseas when the time arrived.

When you pause to remember, take an extra moment to remember the people who take care of getting our military where it has to go today and keep it up and running when it gets there.

Paul Dixon is a freelance writer and photojournalist living in Vancouver.