Features

Bombardier Goes Corporate

The most-turbulent period in Canadian aviation since the cancellation of the Avro Arrow interceptor

March 10, 2020 By David Carr

Bombardier Business Aircraft delivered 142 jets in 2019, including 76 Challengers and 54 Globals. (Photo: Bombardier)

Bombardier Business Aircraft delivered 142 jets in 2019, including 76 Challengers and 54 Globals. (Photo: Bombardier) Bombardier commercial aviation has left the hangar. Since transferring majority ownership of the CSeries passenger jet to Airbus during a bruising legal tussle with Boeing over price discounting, that the Seattle giant would ultimately lose, Alain Bellemare, Bombardier’s chief executive has carved out pieces of the air transport business with surgical precision, including its dwindling regional jet unit to Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and the aerostructures unit to Wichita-based Spirit AeroSystems.

The end was inevitable. The rebranded Airbus A220 had already been pushed to the margins of Bombardier’s corporate jet and rail portfolios. At a mid-January Air Canada A220 launch event in Montréal, Calin Rovinescu, the airline’s chief executive, pointed out that when his airline signed a deal for 45 of the larger CSeries 300 variant in February 2016, it wasn’t clear whether the program could survive. From order to delivery, the Air Canada A220 has bookended the most-turbulent period in Canadian aviation and aerospace since the cancellation of the Avro Arrow interceptor in February 1959. And the dust hasn’t settled. Bellemare also spoke at the Air Canada event, but did not give a hint of the bombshell Bombardier would drop less than 24 hours later.

Home grown, Air Canada and the A220

Commercial exit

Bombardier’s financial turnaround had stalled. The company was more than US$9 billion in debt and would struggle to meet further financial commitments to the A220 in proportion to its 33.4 per cent stake in Airbus Canada Limited Partnership. By Valentine’s Day, Bombardier was out, pocketing $591 million (all dollars in US funds), including an immediate payment of $531 million, and a release from further financial obligations, pegged at approximately $700 million. The remaining $60 million will be paid over a two-year period. As part of the transaction, Airbus also acquired the A220 cockpit and aft production capabilities from Bombardier in Saint-Laurent.

That Bombardier was anxious to cash the Airbus cheque before releasing 2019 year-end financial results speaks volumes of the company’s crushing debt burden. In releasing financial results hours after the sale to Airbus, Bombardier reported that its complete exit from commercial aerospace will generate more than $1.6 billion in cash proceeds once the Mitsubishi and Spirit deals close, and eliminate close to $2 billion in liabilities and future commitments. This includes the Airbus Canada divestiture and relief from the CRJ program and aerostructures.

The sale all but shatters the dream of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, father of the current prime minister, that Canada break out of its role as builder of rugged Beavers, Buffalos and Twin Otters to supply the world’s airlines with passenger jets. It was a vision that triggered the nationalization of Canadair and de Havilland, launched the Challenger business jet and set a course for Canada to pioneer the introduction of the industry altering regional jet.

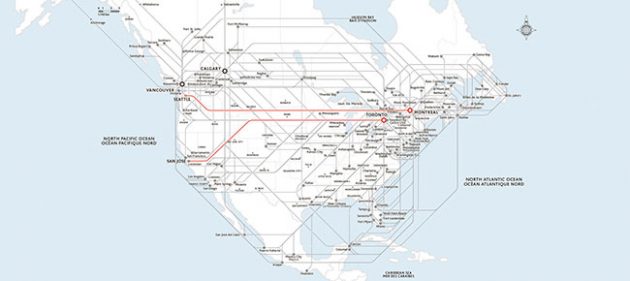

The A220 is a centrepiece of an aggressive strategy for Air Canada to increase its share of U.S. international transit passengers from 1.3 per cent to two per cent; boosting revenues by an estimated $675 million and illustrating the industry impact of the game changing A220 developed in Montreal.

Image: AIR CANADA

It also raises the question, what is next for the one-time aircraft and rail global powerhouse? Since selling the Q400 program to British Columbia-based Longview Aviation, Bellemare has signalled each of the company’s next moves, including a hasty exit from the A220. The path forward is less clear.

Bombardier can be in trains or private jets. It must sell one of the businesses, and perhaps both. Bellemare set up a dual negotiation track to sell either Bombardier Transportation (BT), the rail division, or aviation to potential buyers, including Textron the maker of Cessna Citation business jets. (Textron’s Bell Helicopter subsidiary produces most of its commercial helicopters at Mirabel.) While there is some overlap in the Bombardier and Citation lines, especially at Learjet, Cessna’s Wichita neighbour, acquiring the ultra-long-range Global line would plug a gap in Citation’s product offering. Citation put the Hemisphere, its own entry into the ultra-long-range sector ‘on hold’ in 2019 over concerns with the engine.

Planes or trains

Airplanes appear to have won the day. On February 17, days after disposing of its remaining A220 interest, Bombardier reached a deal with France’s Alstrom to sell BT for between $8.4 million and $9 million. The sale must pass European regulatory hurdles that have already tripped up a merger between Alstrom and Germany’s Siemens. This deal can expect an easier ride. There is less overlap, especially in the two companies’ high-speed rail and signal businesses. Besides, western rail providers need to bulk up again China’s state-owned CRRC, making industry consolidation inevitable.

Whether or not the Alstrom sale gets the green light, Bombardier’s 30-year involvement in commercial aviation is at an end. Nor does selling the train business take a sale of business aviation off the table, regardless of how controversial such a transaction would be in Quebec where Bombardier jets remain a source of provincial pride. Bombardier continues to make money selling higher margin corporate jets. Bombardier Business Aircraft delivered 142 jets in 2019, including 76 Challengers and 54 Globals, and remains a market leader in the ultra-long-range sector. But the business is more cyclical than trains. Unlike a direct competitor such as Gulfstream, a subsidiary of General Dynamics, Bombardier will be more exposed to market downturns.

The guessing game of whether Bombardier should have stuck to its knitting and modernized its regional jet line ahead of developing the CSeries and going nose-to-nose with Airbus and Boeing at the lower end of the A320 and 737 families will continue. It’s a tough call. The A220 is a true game changer that will likely break the sales curse of aircraft aimed at the 100- to-150 passenger segment, including the A318. But the CSeries was too much airplane for Bombardier to take on by itself. The company lacked the resources, especially while simultaneously developing the Global 7500, scale and a global support network to bring the aircraft to market and realize the program’s full potential.

Despite inroads made by Airbus to trim the A220’s bloated production costs, the aircraft’s breakeven point has been pushed deeper into the decade, another factor that reportedly influenced Bombardier’s decision to sell.

Airbus delivered 48 A220s in 2019. The first aircraft to be built in Mobile, Alabama, an A220-300 will be delivered to Delta Air Lines later this year. At the end of 2019, the A220 order book stood at 595 aircraft. Airbus will have capacity to deliver 160 to 170 A220s when both North American production lines are fully operational. Airbus is also considering launching the A220-500, a stretched version of the CSeries that had always been in Bombardier’s back pocket and was perhaps seen by Airbus and Boeing as a more direct competitor to the A320 and 737.

Air Canada’s first A220-300 takes off from Mirabel in late 2019. (Photo: Airbus)

Air France, which last year placed an order for 60 Airbus A220-300s is reported to be interested in the larger variant as part of a strategy to rationalize its cumbersome short- to medium-range fleet. Air Baltic, the launch customer of the former CSeries 300 also sees room for an enlarged version in its soon to be all A220-300 fleet. A third and larger A220, along with the long-range A321neo, would tighten Airbus’ advantage against Boeing and the grounded 737 Max in the hot-selling single-aisle market. Airbus remains noncommittal, but the manufacturer could signal its intentions as early as this summer’s Farnborough Air Show.

Mitsubishi also wants to build the M100 SpaceJet, a direct competitor to the Boeing Brazil (formerly Embraer) E175 in North America close to its target market, although new delays in certifying the M90 SpaceJet, Mitsubishi’s long awaited entry into the regional jet market, will likely have a knock-on effect on the development of the smaller M100. Montréal is a natural fit for both the A220-500 and M100 should Airbus and Mitsubishi go ahead. But in the pay-to-play world of aviation and aerospace, not without a cost. The Quebec government has already given Mitsubishi a $12 million interest-free loan to locate a next generation SpaceJet design centre in the province.

Although Quebec increased its stake in Airbus Canada Ltd. to 25 per cent without any new investment, the value of its share is currently worth less than the $1 billion the government initially pumped into the struggling CSeries. That gap is expected to close if Quebec sells its interest to Airbus in 2026. According to the Montreal Gazette, Premier Francois Legault has been critical of the previous government for buying into the CSeries directly instead of purchasing an interest in Bombardier, and has ruled out any additional cash for the A220. He may not have a choice, especially if the government wants to keep a future A220-500 (and potential future stretches of the airframe) in Quebec that Bombardier has already modelled for Airbus.

Toronto-based de Havilland Canada, which bought Bombardier’s turboprop business last year, sees new growth opportunities for the Dash 8-400 (formerly the Q400) in Asia-Pacific. Montréal remains one of the world’s largest aerospace manufacturing hubs. That is not changing any time soon. What has changed for the most part is that Canada is now a lurer of other manufacturers’ programs and no longer a launcher of our own. A situation that will be compounded should Bombardier sell its business aircraft division an exit transport altogether.